- Home

- About

-

Shop

-

Sewing Patterns

-

Fabric

- Sewing Supplies

- Folkwear Clothing

-

- Blog

- Customer Gallery

- Contact

January 29, 2024

by Esi Hutchinson

We have just reprinted the 303 English Cottage Kitchen pattern again after many years of being out of print. And what I especially enjoy about this pattern is the authentic detailing, which gives tips and how-to's, on stenciling, quilting, embroidery, and how to make your own tatted lace. On the whole this pattern is perfect for tabletop accessories, napkins, placemats, tablecloths and more that just brighten your experience when eating your favorite meals and having a cozy time at home.

Are you looking for a fun and creative way to add a personal touch to your home decor? This blog post will focus on making a stencil out of the floral designs given in this pattern. You can add them to your linens, to your furniture, to your clothes! This post is helpful to refer to in addition to the pattern instructions on stencils.

The earliest evidence of stenciling can be traced back to ancient Egypt, where stencils were used to decorate the walls of tombs and temples. Stenciling techniques were also widely used in ancient China and Japan to create intricate designs on fabrics and ceramics. Its a great way to duplicate designs you want to use more than once.

You will need: Stencil paper, or something sturdy like carboard or cardstock , fabric paint, blade knife, and a cutting mat.

Before you begin stenciling, make sure your surface is clean and free of any dust or debris. You may want to use painter's tape to secure the stencil in place or you can use fabric weights.

Cutting the Stencil

I printed out the stencil and cut out the design. I then taped the design down on to the stencil paper and started cutting the design out.

Make sure your blade is sharp and go slow, try to cut as clean as possible.

I cleaned up the edges of the stencil.

January 25, 2024 1 Comment on (Re)Introducing the 303 English Cottage Kitchen pattern

by Molly Hamilton

We are very excited to bring this special pattern back into print! The 303 English Cottage Kitchen is a treasury of sewing patterns for lovely kitchen items that will make any kitchen feel like a sweet and cozy place to cook and eat and visit. This pattern has been out of print for many years, but was the very first Folkwear pattern I ever owned. It appealed to my sense of creating a home wherever I was. I could imagine making tea and scones, and sitting in a chair by a table with my tea pot covered by a tea cozy and set on a placemat. There would be a vase of peonies and a sweet little tea towel too. Ideally, I would have all this set in a garden or maybe a cozy kitchen overlooking a garden. But it was also perfect for whatever apartment or room I was temporarily renting - to give me that feeling of an idyllic, romantic cottage. Sometimes that is the power of sewing patterns - to help you envision a look, a life, you want. Or to just give your imagination some fun exercise.

We have brought this pattern back as a paper pattern for those who prefer a physical pattern and a PDF version for those eager to sew it as soon as possible. The PDF pattern has copy shop versions (A0 and 36"). There is a print at home file (with all the page numbers noted for printing the different items - so you don't have to print it all to get just the placemat, for instance). The A0 and print at home versions are layered for printing the kitchen items or the apron (and apron is layered by size). And for the first time, we have a projector file as well! Sewing instructions and detailing are also included, of course!

We loved this pattern so much that we even have a few items from this pattern that we have released as free patterns over the years, but 303 English Cottage Kitchen as a whole is exceptional. Not only do you get sewing patterns for a tea cozy, egg cozy, placemats, napkins, oven mitts, tablecloth, and an apron, but you also get all the instructions for adding designs to these items. The pattern provides 8 pages of instructions on stenciling, quilting, and embroidery as well as several interchangeable designs for flowers to stencil, quilt, or embroider onto the kitchen items. Or make up your own designs, and using the instructions provided, add them to the things you make! Plus there are instructions for tatting your own lace! It's not that hard. On a side note, my great grandmother (born in 1898) told me many years ago that tatting lace was her favorite handwork. After seeing this pattern, I can understand why. I thought it was impossible until I read through the instructions here.

Stencil design for 303 English Cottage Kitchen. We will have some tutorials soon about using this pattern.

Stenciling information is given for application to a floorcloth, as well as instructions for how to make a floorcloth. Floorcloths were used in the 1700s and 1800s to protect floors (and rugs) and to insulate rooms, but they were also decorative and often covered in stencil or painted designs.

I don't know what my favorite item in this pattern is, but I do love napkins. And they are a great way to use smaller sections of fabric. They also make wonderful gifts. I really enjoy the biscuit cozy as well. It is so cute and makes presenting biscuits (or scones or cookies) memorable.

Many of these patterns are perfect for using smaller sections and scraps of fabric. And, they make wonderful gifts.

I also find the apron to be romantic! The words Apron and Pinafore are often used interchangeably in this pattern, but I generally call the garment an apron. However, it can be a pinafore, especially if made for girls. The pattern is sized for women (SM-LG) and girls (2-10). We will have some tutorials for sizing the adult apron up very soon. The Pinafore apron pattern can be made so that the skirt buttons in the back and the bib straps are buttoned in the back. And, it can also be made like an apron, with the waistband ending in a large sash which is tied in the back (and apron is open in the back).

All this to say, we are thrilled to be re-releasing this pattern and re-introducing it to you! If you have any questions about this pattern, let us know! We are glad to talk more about it, and we hope you enjoy it as much as we do!

January 24, 2024 6 Comments on My Grey Ultrasuede Version of the Cowgirl Skirt

by Molly Hamilton

When we picked the 243 Rodeo Cowgirl Skirt sewing pattern to feature this month, we got excited about the possibilities. All the different yokes, hem treatments, fabrics, embellishments to choose from! It was almost overwhelming. We had a great time making a Pinterest board of inspiration, and narrowed down some possibilities in this blog post. Esi made a beautiful skirt with some lovely floral silk and Western flair hem applique.

I went a slightly different direction with my skirt. There was a version I saw where the almost one-toned leather skirt laced on the side and had a slightly darker very small yoke. I remembered I had a nice length of grey Ultrasuede that I thought would make a great Western-style skirt. I loved the way the fabric moved and the texture it had. I decided to make View B of the pattern. View B has a skirt that is cut a little bit shorter and has a flounce sewn to the bottom of the skirt. The flounce was a good fit for this fabric because of how well it moves. And I wanted it to lace with long laces on the side.

My Modifications

The Ultrasuede had a little bit of stretch to it, so I decided to cut a size smaller than I normally would. I fall between the Small and Medium in Folkwear's grade rule, so I decided to cut a Small for this pattern. I really didn't want a skirt that ended up being too big because of the stretch. The front and back skirt facings help stabilize any stretch also.

I also moved the back plackets to the left side of the skirt. These plackets are for the laced closing, but I wanted mine to be on the side. This meant that I treated the left side of the skirt as if it were the back in the instructions for the placket and laces. I sewed the back up with one seam instead of putting in any closures. I was a little worried that having the placket and lace on the left side of the skirt would interfere with the pockets, but it really did not. I just had to be careful of not catching the pocket/front yoke in the stitching when I stitched down the plackets. Of course, you can make this skirt with a zip closure (as Esi did and shows you how in her post).

Here you can see the placket I sewed onto the skirt on the left side of the front (it will be on the wearer's left, but here it is on the right side of the skirt piece).

For the front yoke pockets, I wanted my yoke to be one smooth arch, instead of scalloped as the pattern shows. I traced the pattern, used a curved ruler to make a new cutting line, and then had a new pattern piece to use.

Original front pocket yoke with scalloped edges traced on paper.

Here you can see where I connect the two peaks of the scallop with the curved ruler.

You can see the new line drawn with the hip curve ruler. This will be my new pattern piece.

I topstitched all the seams. On the side seams, I pressed the seams to one side and stitched (like a faux flat felled seam), and for the center seams at front and back, I pressed the seams open and topstitched on each side of the seam. I pressed the seams toward the skirt at the flounces and topstitched there. I trimmed the seam allowances for all seams. Since this fabric is a little thicker than a similar cotton or silk, I wanted to reduce bulk where I could. I also used a longer stitch length than normal when topstitching.

Close up of the topstitching at center front and at the flounces.

For the ties, or laces, I used long strips of fabric left over from cutting out my pattern. I used the lengthwise stretch (or "grainline) since it felt the most stable when pulled. If you are making this skirt with laces, I think a soft leather would be amazing, but you can also use twill tape (which comes in many colors) or make your own bias tape. I think bias would work better than a straight grain woven fabric to give some flow to the ties and string.

I did not hem this skirt! The Ultrasuede does not ravel at all, not does it roll. So I just trimmed it up to be completely even, using a curved ruler where I needed to.

Sewing Tips for this Pattern

First, a very important tip for View B that I would use next time for sure, would be to label your flounce pieces clearly. Label front and right and wrong side of fabric as well as center fronts and backs. I had to rip out nearly all of my flounces because I put them in backwards on each piece! That was a huge pain. The flounces have notches that indicate front and back and side. There is one notch for center front, two notches for sides, and 3 notches for center back. But if your fabric is the same on each side (as mine was), it is easy to switch them around. I would even caution that you should label your skirt front and back fabric pieces also. They look very similar and it is easy to confuse them.

The yokes call for a lining in this pattern. You can make and attach them, as Esi did, by folding in a hem and stitching down, but for the front pocket yoke, a fabric lining is best. You can use the same fabric you are using for the skirt or yoke, but if it is a thick fabric, it is not ideal and will add quite a bit more bulk at the seams. I used a Bemberg silk to line my pocket yoke and it worked really well and hardly added any bulk at all.

Also, when placing the yokes on this pattern (or even the hem applique), I would baste them by hand (or maybe by machine) to get them to lay even and flat when you are working. For this yoke, you can stitch from the center to the edge for each side. This technique is the best way to do the yoke. You could also use the sticky seam tape at the seams of the yoke and appliques so they don't shift while you are stitching.

Finally, I hand sewed my eyelet holes for the laces. At first I thought I would put in grommets, but I decided to try hand stitching the eyelets. I cut the holes in the fabric with a grommet punch tool which was by far easier than trying to cut with scissors or even making a hole with an awl. I needed the holes to be big enough to easily sew a blanket stitch around the edge. I also needed to get through several layers of fabric. The punch in the grommet tool was perfect. I punched where I'd marked the lace holes (from the pattern) and I used a tiny pair of scissors to trim any bit of the hole that did not get cut completely.

The tool I used to cut the holes for the laces.

Close up of the hand finished lace holes. This fabric is forgiving and my stitching is not nearly perfect, but you can't really see it!

I really like this skirt! It came out very much as I imagined. I loved finding a great pattern for this fabric. And I am glad to have another winter skirt! Here I am wearing it with my version of the 212 Five Frontier Shirts - and you can see the details of how I made this shirt here.

January 14, 2024 4 Comments on My floral version of the 243 Rodeo Cowgirl Skirt

by Esi Hutchinson

I've been wanting to make this 243 Rodeo Cowgirl Skirt for some time now, so when Molly and I decided to get this pattern ready for re-print I was personally thrilled, however it took me a while to pick out fabric for this project. Molly and I joyfully looked through Pinterest to find some inspiration and there were some amazing options one could do with the shape of the yokes, contrasting fabrics, embroidery, bead and sequins applique, so much to choose from. Check out the inspiration post for 243 Rodeo Cowgirl Skirt here.

I decided to go with this floral silk cotton blend fabric we still have in stock. It is a deadstock Dolce & Gabbana fabric and it is lightweight and stunning! It is not super slick like a charmeuse - it is a bit more like a crepe. If working with silk or silk-like fabrics I recommend looking at this blog post Cynthia Anderson wrote on tips for sewing tricky fabrics.

I always think it is a good idea to use French seams when applicable with delicate fabrics. I used French seams for all the seams in this skirt, except when attaching the top yoke and bottom hem flounce. Here is another blog post you can refer to for how to make French seams.

Another small change I made to the pattern (though it is suggested in the pattern) was to sew in a zipper instead of lacing the back closed. I will show you how I did that below.

This pattern is very straightforward and not difficult at all. The hardest part for me was picking my fabric and deciding how I was going to change the yoke and hem appliques, or if I was going to use contrasting fabric. I'm still wondering if I should change it!

I decided to make up my own yoke by using the shaped yoke piece H and simplifying the yoke with a large scallop. I eliminated the pockets because I felt like the fabric was too delicate for something to be tugging at it from the inside.

I followed the instructions when applying the yoke and used the same fabric for the yoke lining. The yoke is not part of the construction of the skirt, but an overlay on top of it. For my skirt, since I didn't use a contrasting fabric, so gives a slight texture to the skirt as well as a little more body at the top of the skirt.

I made a yoke for the front and back of the skirt. For the yoke going on the back skirt pieces I left the back yoke open for the zipper and just basted the yoke's raw edges to each of their back pieces.

You can barely see the yoke, but since I wanted a little more weight and structure to the skirt on top especially if I used a heavier fabric of the bottom for the hem applique.

For the zipper you will need about an 8" (20.3cm) zipper, you can purchase a longer one if you'd like. If your zipper is longer then you need make a couple large zig-zag stitches over the zipper where your would like it to end. After you've sewn in the zipper your can cut off the excess.

I used a French seam when sewing the backs together to the large dot where the Back Placket would have gone if I was using the lacings.

I used a serger to finish the raw edges of the rest of the seam. Then basted the seam together using a 1/2"/13mm seam allowance.

I placed the center of the zipper teeth on the seam line, I think its helpful to baste the zipper in place before sewing it on. Then I turned to the right side of the skirt and stitched about 1/4 (6mm) away from the seam line on each side and squared off at the bottom right before the zipper stop.

To finish I folded under on the back waist facings 1/2" (13mm) and slipstitched the facing to the zipper like so.

I wanted to give my skirt a western look by using the bottom hem applique that is provided in the pattern. I found a large scrap of light weight brown twill, heavier then the silk of course, but it worked fine.

I didn't use lining for this applique; I just folded under 1/2" (13mm) on all the top edges of the hem applique, clipping at the curves to allow them to turn easily. Then I topstitched it to the skirt hem as instructed in the pattern.

Here is how it turned out. I really do love the look, it fits the western style I was going for. I just don't know if it is an everyday skirt for me, which I would like it to be. Maybe over time I will decide it suits my style. I could also take off the hem applique if I wanted to, or shorten the skirt. Lots of ideas and options!

I am wearing the skirt here with our 210 Armistice Blouse, and it really does make a pretty outfit!

January 09, 2024 3 Comments on Cowgirl Skirt Inspiration

When we were thinking about bringing 243 Rodeo Cowgirl Skirt back into print, we looked at western and vintage western skirts on Pinterest to get some inspiration. We quickly had several styles we loved and ideas for what we wanted to make for ourselves. Esi will show you the silk floral skirt she made (and its variations), and I was inspired to make a simple grey Ultrasuede with a flounce for my version.

But, there are so many great ideas for western skirts, and this pattern really does provide a fantastic foundation for all of these. The yoke appliques are amazing and so versatile. Add fringe or lace, make with the ties or with a zipper, use various fabrics - there are so many options!

FRINGE

Make your own with leather or suede, or add some your purchase. Fringe is quintessential western wear and looks amazing on this skirt. Our pattern even teaches you how to make your own fringe. Or see how to make and apply it here.

This suede leather skirt has fringe just coming from the bottom hem, and has a small embroidery design above it. Pinterest link.

This suede leather skirt has fringe just coming from the bottom hem, and has a small embroidery design above it. Pinterest link.

This cute outfit features the fringe hanging from the hem applique (similar to our pattern). There is also piping used in the waist yoke applique (also similar to our pattern). If you want a shirt or jacket to complete your outfit like this one, check out 212 Five Frontier Shirts and 242 Rodeo Cowgirl Jacket. Pinterest link.

Another similar skirt with fringe hanging from the hem applique. Piping is used on the applique also. Here paired with a western shirt. Pinterest link.

This leather skirt also has the fringe hanging from the hem applique. This skirt also has topstitching at the seams (and belt loops were added). Pinterest link.

FRINGE and APPLIQUE

Fringe and applique go so well together. We found lots of examples of extra fun appliqué on the yoke or hems of skirts, paired with great fringe. You can use the many appliqués in the pattern, or add more of your own to the sides of the skirts. Or, adjust the ones provided in the pattern to fit the look you want.

This one has two layers of fringe and some amazing reverse appliqué on a cotton skirt. Pinterest link.

This skirt has a simple straight hem appliqué with fringe, but also has a great appliqued rodeo scene on the skirt. Pinterest link.

This skirt has fringe on a shaped yoke and appliqué of beads. Pinterest link.

APPLIQUE and EMBROIDERY

The skirt (and shirt) below is stunning with the western themed applique and embroidery.

LAYERS OF FABRIC

Another option for this skirt is to use different fabrics for the appliqued yokes or even as part of the skirt. You could use lace for the yokes or hem appliques. You could use different colored leather or suede on a leather skirt. You could layer several lightweight skirts.

This skirt has a layer of darker leather with scroll work on top of this suede skirt. I also like the lace moved to the side of the skirt. Pinterest link.

This lightweight skirt has a top yoke with fringe and studs and layered with a lace up ribbon. A lace-up yoke is included in our pattern too! You could also use an eyelet fabric for a similar look. I like the fringe at the top of the yoke. Pinterest link.

This skirt shows how you could place lace as the yoke applique for a really interesting and romantic look for the cowgirl skirt. Add lace at the hem instead of fringe. Pinterest link.

Pair the 243 Rodeo Cowgirl Skirt with the Petticoat from 203 Edwardian Underthings for a romantically layered skirt. Add lace or eyelet to the side seams and lace or eyelet to the bottom hem. I love the layered look! Pinterest link.

Make the skirt from a tulle or shear fabric and layer it on top of a pair of shorts. Or make a two layered skirt! Perfect for showing off some pretty farbric! Pinterest link.

We hope this post provides some great inspiration for making your own western skirt. The possibilities are endless (and so fun!). And western wear is very much in right now. My family is always wanting to pair clothes with cowboy boots and Stetson hats, so we enjoy these western looks!

December 31, 2023

While we plan for 2024, we always reflect on the past year and honor our accomplishments. We did a lot this past year, but mostly we enjoyed connecting with you over sewing and our patterns! We absolutely love seeing what you make with our patterns and hearing about your projects. Thank you for being loyal Folkwear customers! Check out the Customer Gallery here.

NEW PATTERNS

510 Passionflower Lingerie Top

262 Spectator Hats - Turban and Cloche

PATTERNS BROUGHT BACK INTO PRINT

224 Beautiful Dreamer (size up from original)

241 Fifties Fit and Flair (sized up from original)

PATTERNS RELEASED AS PDFS

204 Missouri River Boatman’s Shirt

237 Tango Dress (sized up)

253 Vintage Bathing Costume (sized up - also sized up the paper pattern)

241 Fifties Fit and Flair (sized up)

224 Beautiful Dreamer (sized up)

230 Model T Duster (sized up)

We have had a great year at Folkwear. While the sewing market seems to slow down a little bit each year (since Covid), we are grateful that we have a wonderful customer base and fabulous stockists. This year, we also picked up Joann’s as an online retailer of our patterns. And we loved collaborating with Sarah Pedlow of ThreadWritten for embroidery workshops with our patterns! Next workshop is January 20 on Romanian Blouse embroidery. We are looking forward to 2024! We plan to release a few patterns over the year, but our bigger goal for the past few years has been to continue to digitize all Folkwear patterns. We want to have all our patterns available as PDF patterns, and keep in print as many as we can (bringing back out-of-print patterns whenever we can). We plan to continue to work on these goals throughout 2024. We are also planning to release more tutorials for sewing tricky patterns and to cover techniques used in Folkwear patterns. If you have pattern suggestions or tutorial suggestions, leave them in the comments below!

December 21, 2023 2 Comments on Cynthia’s Best Cookie Recipe: Shortbread Cookies with Orange & Dried Cherries

This recipe comes from our 310 Cynthia's Cookie Apron pattern. Cynthia worked at Folkwear for many years and has been a life-long Folkwear fan. She developed the pattern for the apron from a garment that was a staple of her grandmother's who made and wore it all her life - for cooking and doing house and garden chores. An apron to make cookies in should have a delicious cookie to go with it!

This cookie recipe is a variation on Cynthia’s family recipe. Her grandmother loved cordials and liqueurs, so the Grand Marnier was her secret. This cookie is sturdy enough to withstand icing, as well as additional ingredients such as nuts and dried fruit. It is not overly sweet, and so makes a great foundation recipe for changing up the flavors or being made plain.

2 cups all-purpose flour

1/4 teaspoon salt

zest of two oranges

1 cup (2 sticks) unsalted butter (room temperature)

3/4 cup powdered sugar

1/2 cup or more of dried cherries or substitute cranberries

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 teaspoon fresh orange juice or 1/2 teaspoon Grand Marnier

For a variation, add 1/2 cup of pecans

Preheat oven to 325 degrees.

In a medium bowl, whisk flour, salt, and orange zest together. In a separate bowl, cream butter, and sugar until smooth. Add vanilla extract, orange juice, and dried cherries, (and pecans if using) combine.

Slowly add the flour mixture to the creamed butter mixture until fully incorporated. Form dough into ball, wrap in wax paper and refrigerate overnight or at least few hours.

On a floured surface roll dough out to 1/4-inch thickness. Cut using cookie cutter and place on lined cookie sheet. Bake 12-15 minutes or until barely golden on the bottom. Transfer cookies to cooling rack to cool completely.

NOTE: You can also shape the dough into rolled logs about 1.5" to 2" (3.75-5cm) thick, chill, and slice into rounds to bake the same way. I used dried cranberries here, rather than dried cherries. I also find that I had to bake the cookies for 16-18 minutes to get them done with golden brown edges.

Happy Holidays from Folkwear!

These cookies make for great holiday gifting!

December 14, 2023

I won't create a fresh gift guide this year (are you tired, too? I've got a lot of sewing to do!). I'll just direct you to some amazing things we've made from years past, with awesome links to inspire your last-minute sewing gift ideas!

Last year's gift guide can be found here!

Plus here are some great links for extras of the things we recommend in the guide:

December 06, 2023 2 Comments on Free Pattern - Holiday Napkins

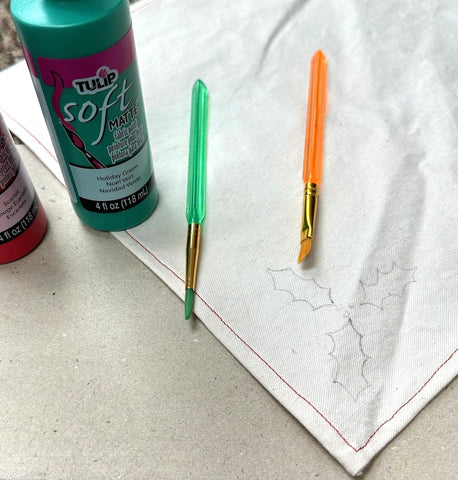

Cloth napkins are a classy and elegant (not to mention, environmentally friendly) way to set a holiday table. These napkins are easy and quick to sew and we have several motifs to add a handmade touch to your napkins - embroider a poinsettia or paint a holly leaf motif. This project will show you how.

Materials Needed:

Suggested fabrics: Medium to lightweight cotton or linen is best; poplin, voile, percale. A solid color is good if you are planning to embroidery or paint, but patterns can be fun also. A holiday-themed fabric would also be fun; quilting cottons come in many holiday patterns.

Notions: Thread. If embroidering, you will need embroidery needles, embroidery floss (DMC or perle cotton #5 or #8) and waste canvas (if doing the cross-stitching). If using fabric paint, fabric paint in your color choice and small paint brushes.

Yardage Requirements

For four luncheon napkins (finish at 15”/38cm wide), you will need 7/8 yard (.8m) of 45” to 60” wide fabric (115-150cm).

For four tea napkins (finish at 10”/25.4cm wide), you will need 3/8 yard (.34m) of 45” to 60” wide fabric (115-150cm).

Cutting

Be sure to wash your fabric before cutting. This will insure that the fabric does not shrink, and you end up with smaller napkins than you expected. Also, if you are embroidering the fabric, you can end up with distorted embroidery if it is not washed first. Press fabric well before cutting.

Cut your napkins with your fabric spread flat. This way you will be most likely to cut on the grain and connect straight edges. Note: to find the true grain and to be sure you are cutting on the grain, pull a few threads from the fabric to show the grain and cut along pulled thread lines. Cut four napkins in the sizes below:

For luncheon napkins - Cut 16”x 16“ (40.6 x 40.6cm) square

For tea napkins - Cut 11”x 11“ (28 x 28cm) square

You can choose to make different napkin sizes. For a cocktail napkin, cut 7” (17.8cm) square, for a dinner napkin, cut 19” (48.3cm) square, for a formal dinner napkin, cut 25” (63.5cm) square. Or cut square napkins at the size you desire, adding 1” to the length and width to account for hem allowance. You will need to adjust your yardage required if you change the napkin size. You could also increase the hem allowance by up to 1/2” (13mm) if you want, for a 1” (2.5cm) hem. Be sure adjust yardage if you are making fewer or more napkins, or making them larger or smaller.

Sewing Instructions

These napkins have 1/2” (13mm) hem allowance on every side.

Press under 1/4” (6mm) along all raw edges of napkin. Turn again on 1/2” hem line and stitch along pressed edge by hand or machine. You can do square corners or mitered corners. For square corners, just press up each edge overlap corners with a square edge.

Square corner. Hem is sewn with contrasting red thread.

For mitered corners, only press under 1/4” hem to start, and place right sides of napkin together at the corners, forming a diagonal, matching folded edges. Stitch a line that is perpendicular to the folded edge of inside of the napkin and goes to the hem edge. Back stitch at beginning and end.

Fold down 1/4" (6mm) on all sides.

Fold napkin at corner so hemmed edges are together and stitch at 90 degrees to the folded edge (as shown here in red).

Stitching is shown here (90 degrees to folded edge), backstitched at each end.

Cut off the extra fabric, cutting at a 90 angle to the hemmed edge.

Clipped corner of napkin.

Open the napkin up, adjusting the corner fabric and press the mitered corner. Then press on all sides 1/4" more.

Do this to all corners and stitch close to the folded inner edge to secure the hem.

You can stitch around the hem with a contrasting colored thread for a festive look. Or, stick with a thread that matches the fabric. For sewing the mitered corners, I do recommend using matching thread.

Now you can embroider, paint, or stencil a design on napkin. And/or add lace, tatting, or other edging to napkin edges for a more Victorian vintage look. See our instructions below for cross stitch embroidery, embroidery, and fabric painting.

For Embroidery

Materials:

Pattern (from our Christmas embroidery pattern):

Cut scrim larger on all sides than design area. Pin scrim in place, matching the angle you want to stitch your design. It can be on grain or on the bias. Baste to the napkin.

Begin stitching

Start at the top, center of the design and work down and outward. Holes in scrim correspond to + on graph, as needle passes through the hole only, and must not catch threads of the scrim. Each graph square represents one Cross Stitch, 10 sts per inch = 10 holes per inch. Use a #10 crewel embroidery needle, and take great care not to catch threads of the canvas, but to pass through the fabric below. Pull stitches up snugly to compensate for removal of scrim. Begin and end threads by running 1”/2.5cm tails under completed stitches on wrong side of fabric.

Stitching

Cross Stitch as indicated on graphs on the design, starting at the center top of the design. It is important to cross the stitches in the same direction, however, you can see in mine that I don't always do that. So it's ok if you miss a direction. Unless someone is going to carefully study your napkin and understand that some stitches are crossed a different way (which they won't do), noone will notice! It is helpful to take each stitch so that on the back of the work so there are only vertical stitch lines (so just go up or down with stitches in the back of the work). This will keep the work neater on the wrong side, which is great for a napkin where the wrong side might be seen. But, again, not a huge deal.

You may work the first half of the stitch in vertical or horizontal rows, crossing on the return course. In small areas it is generally easier to cross each stitch individually (figures on left below).

Remove scrim

When the design is completed, remove basting and fray edges of the scrim so you can grasp the ends one at a time and carefully pull the threads straight out. Pull shorter edges first, holding embroidery near pulling place to avoid distortion. Any scrim threads which have been caught by embroidery must be delicately cut out.

November 29, 2023

by Molly Hamilton

Adding monograms to garments is quite an old tradition. It seems to have originally started as a way to identify things belonging to high ranking people and therefore was also a status symbol. However, eventually monograms also became more practical (though still often for the privileged). By the 16th century, when people sent their laundry off to be washed, having their initials monogramed on the garment allowed it to be easily identified and returned to the correct person. This was especially helpful for undergarments, like the chemise.

Our 223 A Lady's Chemise pattern includes an alphabet in Victorian script that you can use for adding a monogram to the chemise. Of course, you can add a monogram to nearly any fabric - tablecloths, napkins, handkerchiefs, shirts, quilts etc. Monograms can add a bit of elegance to these things. It also adds some personalization to your garments or items. And monograms can make a sweet addition to gifts (especially baby gifts). We have a free pattern and tutorial for a Victorian potpourri sachet, and it is perfect for adding a monogram to. Small and simple, and you can try out different lettering if you make a few of them. Monograms can also be used to sign a special garment or quilt, using simple stem stitch, to identify the maker of the work (of art!).

There are many options for how you make a monogram. You can make your own design (as monarchs of old did) with your initials, combining them or overlaying them with your own special flourish. You can make very plain, simple letters in a straight stitch or embellish them in fancy fonts. Fonts can be romantic and Victorian with lots of scrolling or it can be block script or Art Deco style fonts. You can cross stitch your letters - using waste canvas or free-handing the letters. You could couch stitches so that the thread looks like handwriting. I learned shadow work at a ThreadWritten monogram workshop which was very interesting and simple. On a side note, I highly recommend Sarah's workshops at ThreadWritten, and her monogram workshop is fun and informative.

Medieval monograms from Byzantine empire - these were made of stone and used to press lead.

Royal monogram on metal from the 1700s in Europe. These combined letters (and a number) into a monogram to identify the royal.

White on white embroidered monogram in block letters with chainstitch and knotted embroidery around it. Pinterest link.

A simple block letter monogram made with satin stitch. Pinterest link.

At deco style lettering that can be used for embroidered monograms. Pinterest link.

A fancy script, cross stitched monogram. Cross stitch can also be used to make very simple letters. Pinterest link.

This is a handkerchief that I have that has been in the family a long time. The H is embroidered in scroll and with a nice satin stitch.

This is on the other side of the same handkerchief. Most likely commemorating a marriage with the year of the marriage. The letters are a bit fancier and much smaller and also done in satin stitch. Note the threadwork hem also. I think the letters are MAS and OGH.

Monogramming Your Garment

Monograms don't have to be perfect. They can be playful; and the imperfections are beautiful also.

Most traditional monograms are made with satin stitch over an outline of backstitch or split stitch, as you can see in many above. You can also do lines of stitching in chain stitch or stem stitch.

If you don't know these stitches, we have several of them shown on our blogs or YouTube channel. Many of these stitches are also taught in our Mexican embroidery pattern.

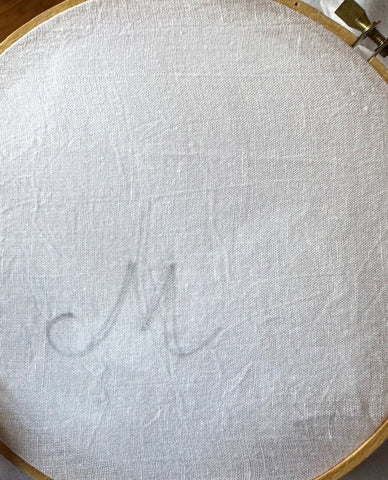

Starting the Monogram

First, you usually add a monogram to a garment after it is made. You can draw the monogram design freehand on your garment or you can trace it. For more information on transferring embroidery designs, find our blog post about it here. I often use a fine, water soluble marker to draw my designs for monograming. Sometimes I'll even use a sharp pencil on a light-colored fabric (as I did below), knowing I will stitch over the markings.

Thread for monograms is usually perle cotton or 2-4 strands of DMC floss. I often use DMC floss, but perle cotton gives a little bit of a different feel and look. Often undergarments (and handkerchiefs, etc.) were monogramed in the same color as the fabric - usually white. But, you can use any color you want. Variegated floss is very pretty and contrasting thread will stand out more. Multicolored monograms are fun. It is up to you to decide the look you want.

I also like to use a hoop for monogramming. I don't always use one when embroidering, but the hoop keeps the fabric taut and makes it easier to see the outline of the letter. It also helps me with tension when I am doing satin stitching (it is not my strongest skill).

The Stitches

I am going to show you how I did monogram similar in design to the ones in our 223 A Lady's Chemise pattern, using a Victorian script and satin stitch over a straight stitch (back stitch) with stem stitch when the design gets narrow and curved. I am using a contrasting thread so you can see the design and stitches easily.

I started by drawing a letter in pencil that shows where the wider part of the letter would be. I could have made this whole letter with stem or back stitch and kept the letter the same width all through, but I wanted to experiment with the satin stitch also.

I started my monogram with a knot at the end of my thread, but there are other ways to secure your thread, including making a few small stitches inside where the satin stitches will go.

Below are the stitches I used for this monogram.

Stem Stitch. I started with a stem stitch. This stitch gives a little more depth to the lines and helps make a pretty curve, in my opinion. Work stem stitch with a simple forwards and backwards motion, always keeping the working thread to the same side of the needle with each stitch (usually below the line, or to the outside of the curve).

Bring thread up through fabric and take one stitch about 1/4 inch (6mm) up.

Bring thread back up for the next stitch about 1/4" (6mm), and go down about half-way back on the first stitch, staying to one side of the thread.

Continue this way, staying on the same side of the thread each time and keeping working thread to the same side).

Backstitch. This simple stitch produces a straight uninterrupted line. I transitioned to the backstitch in the areas that would be covered with stem stitch. This is a good stitch to outline the area to be covered with satin stitch. It also provides a bit more relief to the design when covered in satin stitch.

Bring needle up slightly ahead of starting point (1/4" (6mm) or less) and take it back down into the fabric at the starting point. Bring the thread back up again one stitch length (1/4" (6mm) or less) ahead of the first stich and take it back down, meeting the first stitch, as you can see below.

I continued the backstitch on each side of the wider parts of my monogram.

Satin Stitch. These are simple straight stitches worked closely side by side to cover an area. Bring the needle up on one line, then down on the other one. Bring thread up again next to the first stitch and work second stitch beside the first, and repeat, filling the area and adjusting stitch length as needed.

To End the Monogram (or your strand of floss)

You can thread the last bit of your thread through the stitches that you've already made in the back of the monogram. This is an easy way to secure your thread. Then clip any remainder floss.

And that is about all there is to hand embroidering a monogram. These are handmade touches to your garments or linens that are special and commemorative. And they can be fun, fancy, plain and simple, and sometimes wonky - and that is part of their beauty. Have you hand sewn monograms? What have you added monograms to? We love to know!

November 24, 2023

Folkwear's annual Black Friday Sale goes until Sunday the 26th (midnight EDT)! Use code THANKS2023 to save 25% on all sewing patterns, fabric, and sewing supplies. And, just in time for the sale, we got some exciting new fabrics in recently. I will show you the some of these new fabrics and will give suggestions for what Folkwear patterns they will be great for. These fabrics are beautiful and very fitting for winter, and some are well suited for the coming spring season. If you want to get some fabric for sale, today through Sunday would be a great time, especially while we still have these gorgeous fabrics in stock. Don't forget that we sell our fabric by the 1/2 yard, so each unit is 1/2 yard (2 units is 1 yard, etc.).

We ordered several colors of these stunning wool/linen woolsey fabrics from Merchant & Mills. I've been eyeing them for years and now that they will soon be discontinued, we decided to wait no longer to get them in stock. These fabrics would look amazing for long skirts, light weight jackets, shirts, pants, or simple dresses. They are soft with a nice drape, and have different colors on each side of the fabric. I can imagine this used for 216 Schoolmistress Skirt, 148 Black Forest Smock, Basics Overcoat, or a pair of pants or overalls from 240 Rosie the Riveter. Both sides having pretty color would also make it a wonderful fabric for the 271 Sunset Wrap (which also makes a great gift). These woolseys would also be beautiful in 270 Metro Middy Blouse, 209 Walking Skirt, or 233 Glamour Girl Dress. And for pants, these patterns would be great: 119 Sarouelles, Basics Pants, 250 Hollywood Pants, 112 Japanese Field Clothing.

This fabric also comes in a dark burgundy, teal and a dark brown color.

Woolsey Wool Linen blend - Black Coffee

Wool Linen blend Woolsey - Oxblood

We still have some beautiful Italian Wool in stock. This Italian Yarn Dyed Wool is very soft and lightweight (like a suiting weight) with a beautiful glow of muted warm colors. Use it for 256 At The Hop, 209 Walking Skirt, 233 Glamour Girl Dress, 222 Vintage Vests, 132 Moroccan Burnoose. I think it would be really cute for 251 Varsity Jacket and for 123 Austrian Dirndl as a warmer dress.

I really missed having lots of sanded twill options in our collection, so we ordered more! Our new stock is bright, fun, and rich in color. Get ready for this bright orangey-red color called Chore Red!

I think these colors are fantastic, and I think sanded twill is the best! I really want someone to make 231 Big Sky Riding Skirt out of these twills or even something from 240 Rosie the Riveter, 229 Sailor Pants, 126 Vests from Greece and Poland, 270 Metro Middy Blouse, or the Basics Pinafore Dress.

I am definitely buying some of this green sanded twill fabric during our sale. It would be classic for 130 Australian Bush Outfit. I would love it for 230 Model T Duster and 231 Big Sky Riding Skirt. This slightly heavier twill would work nicely for 133 Belgian Military Chef's Jacket, 242 Rodeo Cowgirl Jacket or 243 Rodeo Cowgirl Skirt - PDF.

Also, any of the twills would be great as cushion covers, durable and easy to clean, try it with 305 A Japanese Interior.

Cotton Sanded Twill - Chore Red

Sanded Twill - Otto Green (12oz)

Cotton Sanded Twill - Prussian Blue

We also got in quite a few Jacquard Cottons from Merchant & Mills, including some new ones. These jacquard fabrics are made up of layers of cotton, with a jacquard weave that gives it a quilted look and feel. They are actually quite warm. I've made a pair of sweatpants from a grey Jacquard we have and wear them on really cold days. These fabrics below would fit well with 305 A Japanese Interior, 206 Quilted Prairie Skirt - PDF, 106 Turkish Coat, 138 Child's Australian Drover's Coat. Molly made the 137 Australian Drover's Coat for herself out of our quilt-like Jacquard, check the blog post here. You can also see the 206 Quilted Prairie Skirt she made from one of the jacquards in this post as well. These fabrics are great for bedding as well - Molly has a beautiful blanket she made with a length of this fabric - bound on each end with a pretty binding she made with scraps of Liberty of London lawn.

This layered cotton has a jacquard weave, with fine cotton on top, no batting in the middle of this cloth, the inside is made up of a series of thicker yarns and the reverse is a gauzy cotton.

Marine Blue Jacquard Cotton - Merchant & Mills

We also have these two Viscose Challis vintage floral print fabric. They are very soft and lightweight. They would be perfect for vintage inspired garments like the 252 Beach Pyjamas, 510 Passionflower Lingerie, 241 Fifties' Fit and Flair, 247 Lindy Shirtdress, or 205 Gibson Girl Blouse.

Viscose Challis - Vintage Teal Floral Print

Viscose Challis - Olive Vintage Floral Print

These are only a few of our new fabrics, so go ahead and get shop our fabric while it is on sale! Christmas is coming up so it would be a good time to get some handmade gifts ready! Check out our gift guides from years past: last year's gift guide, gifts to be sewn, and 2021 gift guide.

Enjoy shopping and have a wonderful time with your loved ones!

November 21, 2023 2 Comments on How to finish the 223 A Lady's Chemise neckline with lace eyelet

by Esi Hutchinson

Hello! I hope you saw Folkwear's blog post I wrote about making the 223 A Lady's Chemise into a blouse. If you have not read it you can check it out here. Recently, I made another chemise to add to the Folkwear sample collection. We wanted a sample that was made of an organic white cotton voile -- a more authentic, or traditional/historic, version. We used View A, which is a bit off the shoulders (though can also be worn wide on the shoulders). Traditionally, the chemise was an undergarment made of light to medium weight cotton or linen and was often white. The lace and eyelet/beading was used to finish the neckline and sleeves openings and add a bit of a romantic touch. For this chemise, I used an eyelet lace that we already had in our stash, and the voile from our fabric collection.

Our eyelet lace already had the ruffle attached (it was eyelet/beading and lace in one!), so I had to modify the instructions to finish this chemise. The instructions have the neckline and sleeves finished with a bias binding, eyelet or beading, and a lace edging - all of which come together to provide a clean and romantic finish. We imagine that often times, you use the notions, like lace or eyelet, that you have in your stash (or have inherited). So when you go to make a garment like this one, you look at what you already have, especially if it is inherited or heirloom pieces. And this means that what you have on hand might not be exactly what the pattern is calling for. As in this case. So, you have to modify how the neckline and sleeves are finished so that you get the look you want with the pieces you have. I will show you how I assembled this eyelet lace to the neckline, and maybe that can help you in a similar situation.

Close up of the eyelet (beading) lace used.

The cotton voile I used is very lightweight so I finished all the seams with French seams. This seam finish is authentic, and it also looks more professional in my opinion. It also really gives the garment an heirloom-quality feel. French seams are also good to use with delicate fabrics like this voile. Here is a blog post on our site you can refer to if you don't know what and how to use a French seam: How to Sew a French Seam.

French seam on the inside side of this chemise.

French seam on the inside side of this chemise.Adding the Lace

Instead of first sewing on the eyelet lace (which is also called beading in the instructions), I first sewed on the bias binding like the instructions say. The eyelet I use is finished on each side with lace, so I did not need to "sandwich" it with the binding and lace edging.

I trimmed the seam allowance and pressed the binding away from the bodice, and turned it to the inside. Then I topstitched the pressed edge of the binding through all layers. This finishes the raw edge of the bodice. I did the same to the sleeves.

I pinned the eyelet lace so that the inside edge of the lace (where the eyelet changes to lace edging) was about 1/8" (3mm) from the top edge of the bias binding. I stitched the lace down on that line. And I did the same for the sleeves.

Inside the chemise. You can see the stitching line about 1/8" from the top of the bias binding where the eyelet lace is stitched down.

VOILA! Finished!

VOILA! Finished!

You can purchase ribbon to weave through the eyelet or make your own using a binding tape maker and fine fabric. I used a satin store-bought ribbon for this sample. I finished the ends of the ribbon by turning them under twice by 1/4" (6mm) and stitching.

I have a few more pictures of the finished 223 A Lady's Chemise (View A) below. This was a fun project and I enjoyed looking through our lace collection to find something that worked for this chemise.