-

Sewing Patterns

-

Fabric

- Sewing Supplies

- About

- Blog

- Gallery

-

October 26, 2021 2 Comments

by Cynthia Anderson

Making piping is not difficult, and piping can add lots of interest and dimension to your hand-sewn garments or homegoods. In this blog post, I am going to show you the basics of making your own piping. Several Folkwear garments can have piping added to them, and actually encourage sewist to do so (145 Chinese Pajamas, 242 Cowgirl Jacket, 503 Poiret Cocoon Coat, etc.). I hope you will be inspired to try it after reading this post, or if you have, that you may pick up a tip or two.

What you need for making your own piping:

Making your own piping is not hard, but you do need to calculate how much your project requires. Believe me when I say there is nothing more frustrating than taking time to make piping and then not have enough. So, whether you make your own or use pre-made piping, be sure you have all you need plus a bit more. If making your own piping be sure to calculate and purchasing extra fabric yardage.

Fabrics to Use for Piping

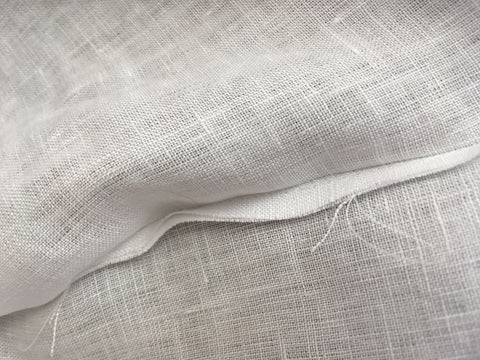

Ideally, piping should be cut on the bias, which allows for a bit of fabric stretch and give, enabling a smooth edging around curves and corners. For this reason light to mid-weight fabrics work best for garment making. If a fabric is too thick or stiff, it simply will not have a flexible “give” and will not lay nicely going around corners or curves. Heavy fabrics are used for piping on large projects like upholstery cushions. The thing to keep in mind, is application. For clothing, I particularly like to use fine cotton, linen, wool, and silk for the piping. I don't recommend using knit fabrics or fabrics that are loosely woven. My rule of thumb is to match the weight of the piping fabric to the weight of the fabric I am making the garment from. If you are unsure about what weight or fabric to use when making piping, take the time to experiment with different weights of fabrics to get an idea of how they behave.

Since a bias binding strip is the foundation for piping, have a look at Molly’s demonstration of how to make continuous bias binding or bias tape in this YouTube video. To make piping you often need a very long strip of bias tape and this is an excellent way to make it as it all comes out as one long strip.

Making Piping

If you used the continuous method to make bias tape you are probably all set with enough bias tape. Another way to make bias tape is to cut enough 2-inch (5cm) wide bias strips from a fabric of your choice to make the length you need, plus a tad more for extra measure.

If not doing the continuous bias tape method, pin and stitch the strips right sides together end to end to make one continuous strip.

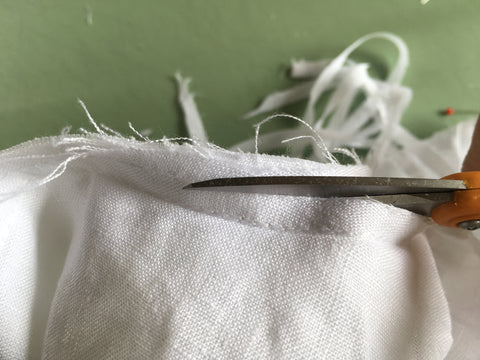

Trim to the extra fabric to create clean edge and press the seams open.

With either method of making bias tape, fold the bias strip wrong side together along the length, with a long piece of the cording sandwiched in between the fold.

Tip: The cording should be longer than the bias tape. Leave a bit of extra cord length at the ends of the piping until it is applied to your project to help keep the cord from pulling out.

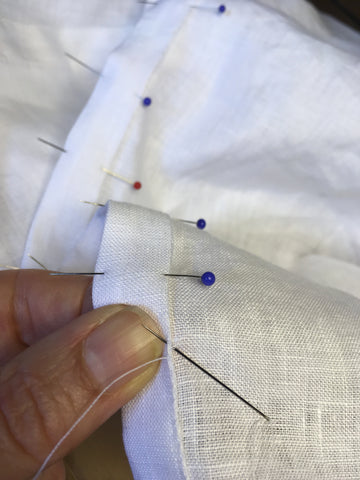

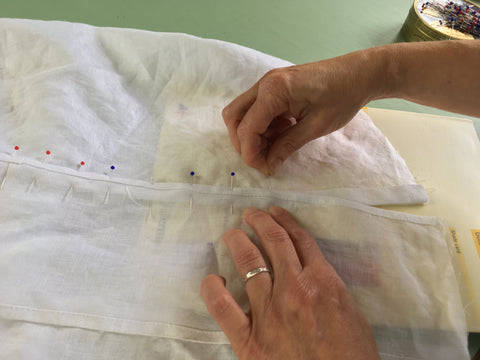

Be sure to line up the long raw edges and pin or baste the fabric in place close to the cord. Machine baste the fold closed to help hold the cord in place and to make the final, more precise, machine stitching easier.

Next, using a zipper foot, which will allow you to stitch closer to the cord, stitch through both layers of the folded fabric as close to the cord as possible, but not so close as to catch the cord in the stitching. It helps to stitch close to the cord to ensure a good alignment when adding it to the seam allowance.

Tip: Use a thread color that matches the fabric or that blends in well. You don't want to have visible stitching in the piping.

You are now ready to apply your handmade piping to your sewing project!

October 15, 2021 2 Comments

This is day ONE

To learn how to make the piping, click here

by Cynthia Anderson

Today we are starting a three-day sew along for our 503 Poriet Cocoon Coat! This coat has a simple construction, yet it is unique and it can help to have some extra instruction and photos to show you how the coat comes together. As well as how the details can be more easily implemented in the coat construction.

Folkwear’s 503 Poiret Cocoon Coat Pattern is one of Poiret’s most iconic designs. Poiret drew his inspiration from the theatre and Eastern Asian culture to create a coat that is just as much a show stopper today as it was in the early 1900’s. Poiret understood the French Public’s desire to see and to be seen as part of the new avant garde, whether at the theatre, a cultural event, or art galley exhibition. Poiret saw his clothing designs as an extension of the wearer’s experience, allowing them to be part of the drama and to participate in the spectacle of being seen. We may owe “Red Carpet” phenomenon to Poiret!

Check out the How Poiret Made History and the Cocoon Coat blog to learn more.

Poiret brilliantly introduced all his designs in the most luxurious and beautiful fabrics of the day, using radical and exuberant attention-getting color combinations. He was not afraid of pairing clashing and bold colors, which only added to the excitement that embodied his bold new approach.

Poiret’s use of layering details also added to his unique aesthetic. He used embroidery, beadwork, appliqué, avant garde painting techniques, and even the more crude aesthetic of stenciling on fabric. Fur trim was often used in radical ways, as in the Lamp Shade Dress. This level of innovation set his reputation as an artist, encouraging Poiret to crown himself the King of Fashion. His willingness to push boundaries seemed to elevate each new design to a wearable work of art.

To help you make the Folkwear 503 Poiret Cocoon Coat even easier, it’s construction is broken down here into three easy to follow sewing days. None of this is difficult, but it is always fun to have a bit of help and learn a few tips along the way.

The Sew Along Schedule:

Day One: The first blog is is simply to help inspire you, provide suggestions on fabrics to use, and getting started with the basic layout and construction. You can make a lining too.

Day Two: How to add the neck band and optional pipping.

Day Three: How to finish the coat by adding the lining, adding the optional decorative ribbon, hemming the sleeves, and adding a finishing closure touch.

Sizing

First, see the size chart below (or linked) to determine your correct size and the yardage that corresponds to your size. Take note that there is quiet a bit of ease built into the pattern, allowing it will fit larger sizes than the pattern indicates.

Use the "Lengthen and Shorten" line if you need to adjust the length. See the “Fitting Your Pattern” in the instructions inside the pattern for more details.

Choosing Fabrics

The same fabrics that made the Cocoon Coat such a head turner when it first introduced, are still excellent choices today. Poiret understood the dramatic effect of using velvet and silk to not only create a sense of enveloping luxury, but in how beautifully these fabrics made the light dance making the wearer appear illuminated. You can make the coat using a double layer of differing silk weights or a combination of velvet with a silk lining for a truly decadent coat or robe. For best draping results mix any combinations of medium to heavy-weight fabrics such as velvet, silks, rayon, or jersey. Typically, use a heavier weight fabric for the coat and a lighter weight for the lining. Have fun and use different textures and colors combinations for outer coat fabric and lining fabrics for stunning results.

Fabrics like Polar Fleece would make a unique and fun garment for lounging about or giving an outdoor activity a new twist. Just imagine wearing a cocoon coat made of polar fleece and lined with silk to a football game or socializing around an outdoor fire pit with your friends and neighbors. Rip-stop-nylon would turn the Cocoon Coat into a unique windbreaker or beach cover up.

Any fabric that has a nice drape is an excellent choice. Besides the usual offering in cotton, wool, and linen, consider fabrics like a soft corduroy in a cotton blended. Look for cozy cotton and wool blend flannels. Silk/cotton organdy or a gauzy open weave fabric to make a truly unique cover-up for warmer weather, especially if you leave it unlined.

Follow in Poiret’s footsteps by using the Folkwear 503 Poiret Cocoon Coat Pattern to show off your skills in embroidery, quilting, dyeing, appliqué, or hand painting. Or use Pre-embroidered fabrics, metallic fabric, and quilted fabrics. This coat makes the perfect canvas for making your own wearable work of art and honoring the creative genius that inspired fashion history.

Note that fabric less than 45-inches (114 cm) wide will not work for this pattern because the pattern pieces are too large to fit on smaller width fabric. Just keep this in mind when choosing a fabric.

Getting Started

To get started in making your own 503 Poiret Cocoon Coat you will need:

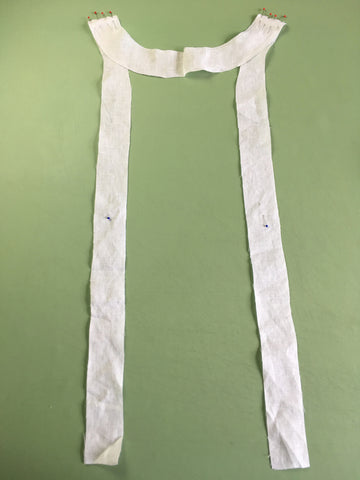

For this sew along, I will be using silk duponi as the coat body fabric, a cotton/linen sheer woven fabric for the lining, and a striped cotton/rayon velvet for the collar.

Note: I like to use the selvage when possible, especially when using a delicate fabric. For this coat I am using the selvage of the fabric to help create a sturdier center back.

The Basic Construction

The Cocoon Coat is deceptively simple to make, but it is help to be familiar with the layout and construction before getting started. The main body is comprised of two pieces cut from Coat Body A. Pattern Piece A includes portions of both the front and the back of the coat. It helps to know there are no side seams in this coat design, instead the two Coat Body A pieces are stitched together at the center back seam. The sleeves are created by folding them in half and sewing up the seam. The front pieces overlap equally to create a simple balanced closure.

Cutting the Pattern and Fabric

You will need a large area to lay out the fabric and pattern for cutting - a large table or the floor.

Helpful Hints

To avoid disappointment please read the information below before cutting the fabric out.

Laying Out Fabric With a Directional Considerations

If you are using a fabric with a directional nap like velvet or corduroy, be sure that both pattern pieces are laying on the fabric in the same direction. Note: If one of the pieces is flipped up-side-down then the nap will go in opposite directions on each side which will look odd.

If using a fabric with a large directional (printed or woven) repeat design you will likely need more fabric to allow you to match the design. Due to this particular coat design, you should try to match the pattern at the back seam. And honestly, you could cut the coat without a back seam if you have fabric that is wide enough. You may also find it helpful if to trace two copies of pattern piece Coat Body A. Having two pieces to work with will help take the guess work out of matching the pattern design of the fabric or aligning the pattern.

For help in understanding how to matching large repeat design patterns… See the blog: Helpful Hints in Making the 122 Folkwear Hong Kong Cheongsam.

Cut fabric for main body of the coat, lining of the coat, and collar. Be sure to transfer all pattern markings from the pattern to the fabric with temporary markings or tailor's tacks.

STEP ONE: Coat Body

Note: You will use the same Coat Body pattern piece for the main coat as for the lining, and repeating the same steps are below. I am going to make a lining, but will resist providing photos since I would simply be repeating the process.

Darts

Start by making the darts at the neck of the coat. Transfer the lines, dots, and circle provided on the pattern to the wrong side of the pattern piece of the Coat Body.

Working on the wrong side of the fabric, fold the fabric so the lines match. Use pins to align and match the lines and to hold the fabric securely in place. At the neck edge of the Coat Body A, start the stitching at the dot with a backstitch, continue stitching using the line as a guide, ending at the circle point with a long thread tail. Tie off the thread tail with three knots.

Press the dart away from the center back.

Center Back Seam

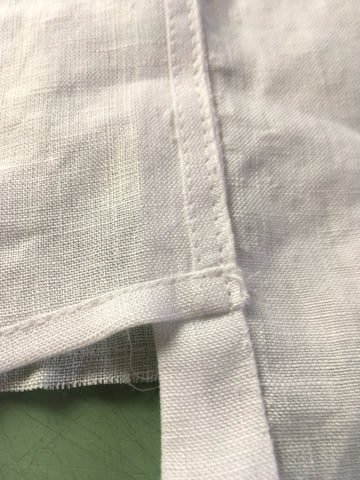

With right sides together, pin and stitch the coat bodies together along the Center Back seam, matching notches 1 and 2.

Press the seam open. Notice the selvage was used to create strength in the center back seam.

Repeat for lining.

Sleeves

Fold the sleeve in half lengthwise (perpendicular to the sleeve hem). Stitch the sleeve seam, matching notches 3 and 4. Clip the curves and press the seam open.

Repeat on opposite sleeve.

Repeat for lining.

I hope you have enjoyed the easiness of the construction of the 503 Poiret Cocoon Coat so far.

In the next Sew Along blog we will cover how to make the collar and learn how to add the optional pipping, plus a few more tips and hints.

FYI: The Folkwear 503 Poiret Cocoon Coat Pattern and PDF are both on sale until Oct. 31. Thanks and see you again soon!

October 12, 2021

Our 143 Japanese Michiyuki pattern is a versatile and elegant piece that can be styled for a variety of functions. Cottons for a light windbreaker or beautiful smock, flannels for a warmer jacket, and silks for a smooth evening coat are all great choices for constructing this piece. Here are some suggestions we've curated for exciting takes on this beautiful pattern, as well as some information on sourcing and choosing Japanese silks for a more authentic garment.

According to Hanami: Mai's Blog, Michiyuki are more of a protective, traditional garment. Like a coat to be worn over the kimono, their function is predominantly for warmth and to keep clothing from getting damaged. Because of their utility, Michiyuki tend to be subdued in their coloring and simple in patterning, which also would make them easier to coordinate with multiple different ensembles. However, I feel this garment has the potential to be styled in a way that is more statement-piece friendly, and have chosen some fun fabrics to explore that avenue.

To start, we have this subtly adorable cotton dobby fabric from Hart's Fabrics that blends traditional and modern in its patterning. The wave/scale pattern is a mainstay of Japanese aesthetics, but the twist is this one includes cats in it. I can't get over it, it's too cute.

Next, also from Hart's Fabrics, is a tasteful Autumn stripe fabric. This cotton flannel would make for a cozy and warm jacket.

Bolt's Fabric Boutique has a precious floral gingham print that would make for an adorable Michiyuki with a slightly playful edge.

Also, making the Michiyuki out of rainwear fabric would make a really beautiful and unique raincoat. This navy rainwear, cotton with latex backing, from Marcy Tilton would be very nice, especially paired with some stand-out buttons.

Finally, for a more traditional route, you could look to source authentic Japanese kimono silk. Luckily, there is an abundance of deadstock or otherwise unsewn kimono fabric to be found online. Places like Ebay and Etsy are good choices, though a bit transient in their offerings. A couple keywords to be aware of in your search: You would find good results searching for Chirimen, or Rinzu silks. Both are types of silk that are different, but appropriate for use in this application. Additionally, be careful not to buy fabric that is intended for the obi. An obi is the waist sash that is tied around the kimono, and will be too thick for sewing a Michiyuki. You can get a sense of obi fabric if it is thick, has a lot of embroidery or metallic threads, and looks like it is designed to sit sideways with its motifs.

That said, here is an authentic kimono silk bolt from ebay with several yards available that would be perfect for a Michiyuki or other Japanese garment. Since kimono fabrics are regularly singular bolts, be sure to check with the seller or the listing to make sure it will have enough yardage for what you need.

October 05, 2021 2 Comments

If you are taken with the flair in which Phryne Fisher wears the glamorous coats in the PBS series Ms. Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, or relished in the flamboyant entrance of Shirley MacLaine’s character Martha Levinson in Downton Abbey, then you owe your adoration to Paul Poiret. If you dream of possessing a Cocoon Coat of your own, then Folkwear has the pattern to make your dreams come true. To best appreciate the Folkwear 503 Poiret Cocoon Coat one can not separate it from the extraordinary man that designed it and the time in which he lived.

The extravagance of the Belle Epoch or The Beautiful Age would give way to one man’s radical vision of the modern world, enabling him to distill and reflect back the desires and ethos of a new modernity. For the first time women were given the opportunity to dress according to how they saw themselves, forever changing fashion. While Worth was credited for founding haute couture, Poiret (1879-1944) is recognized for completely transforming it, crowning him the first “modern” designer. Paul Poiret revolutionized women’s fashion, dismantling six-hundred years of how women in Europe wore clothing. Except for a brief Classical Grecian influenced moment during the French Revolution, the female body was divided into two separate halves, like an hourglass. Poiret was frustrated with the lack of creativity in how women dressed and set out to change things.

Many of Poiret’s ideas came from his observations as French society’s became more restless for change. Paul Poiret ushered in many firsts that were a culmination of his multifaceted view of what modern life should look like. Many of his revolutionary ideas continue to to shape our ideas today. Poiret cultivated an aesthetic that was expressed through not only the clothing he designed, but through his recognition that fashion was a natural continuation of a life-style. He designed not only clothing, but furniture, textiles, interiors, and fragrances. He made headlines for the legendary parties he threw and in the way he traveled around the world to showcase his collections. Poiret compared his work with the work of Picasso and counted among his friends and sometime collaborators numerous artists of the period. He was inspired by the the Ballet Russe and collaborated with Sergei Diaghilev. The Fauvist painter Francis Picabia was a good friend and the two shared a love of bright colors and bold pattern. Modern art in all its forms would remain a driving force in inspiring Poiret’s work.

At the turn of the century, the world was changing quickly and Paul Poiret was eager to make his mark. He drew his influences from every corner of the globe. His desire was to create a new vision of modernity, which encompassed freeing silhouettes to reflect new attitudes. He relied on drama and spectacle to catch the attention of Parisian society. A Classical Grecian dress designed for Isadora Duncan created a frenzy for the Ancient Greece silhouette that the designer is best known for. He introduced a pants derived from a costume worn by Egyptian dancers girls that shockingly exposed women’s legs (think Sybil’s Harem pants in Downton Abbey). The rage for everything Asian-inspired was in part fueled by Poiret’s theatrical geisha kimonos.

Unfortunately, Poiret failed to acknowledge these influences let alone give credit where credit was due. He took inspiration from other cultures, molded them to his extraordinary vision, never acknowledging their origins.

One of the most distinguishable designs was the Lampshade dress which was paired with the infamous Hobble Skirt. The exuberant costumes and productions of the Ballet Russe not only inspired the designer, but he would use the stage in a brilliant marketing scheme to reveal his own designs to the French public. He even used his own wife Denise Boulet as a model, catapulting an ordinary young woman into a celebrity muse.

Poiret’s vision for the modern woman did not include the constraints of the corset. While he is often credited with freeing women of the corset, it was actually, Madame Vionnet (an early mentor of Poiret) who first abandoned the rigid structure of the corseted figure. Poiret was patient with society's hesitancy to completely discard the corset. He let the recommendations by doctors over medical concerns and the principles of the Suffragettes help to pave to way. Poiret did claim to be the inventor of the brassière. He explained that his designs celebrated the freedom from structured undergarments. This brassière was made of a thin band of fine cotton or silk that covered the bust and was held in place by narrow shoulder straps. Fashionable women took to the new comfortable physical sensation without much hesitation. Poiret gave women permission to free themselves from corsets while being mindful to provide them with a little something to help maintain their respectability. It would appear Poiret was calculating in how he unveiled his visionary ideas, being careful to not upset the applecart all at once.

Poiret was frustrated with how he saw fashionable women’s clothing relegated them into living dolls. He intend to upend this feminine ideal with his own vision. Poiret would replace tedious pattern construction with new silhouettes derived from draping techniques. Poiret’s designs were revolutionary in their complete abandonment from the rigid and highly sculpted bodices and nipped waists that had confined women’s bodies for hundreds of years. He shifted the focus of the female figure away from the waistline to a long, lean line, beginning at the shoulders and ending in a narrow hem at the ankle. Poiret’s fluid and sensual designs were intended to free women and as he explained,

The designer was not without a contradictory misstep, taking the sleek silhouette to an absurd extreme with the design of the Hobble skirt. The skirt was so tight from the knees to the ankles that sometimes the legs had to be taped together to prevent splitting the skirt while attempting to walk. Poiret himself commented that he had “freed the breasts but shackled the legs”. A torrent of outraged protests from the press and a Papal condemnation led to slit skirts, buttoned hems, and pleats that allowed for mobility. Despite or maybe because of the uproar, the narrow silhouette was here to stay.

The basic shapes of Poiret’s designs are fairly simple. He was not revered for his construction techniques, proving you do not have to be an engineering genius to produce amazing results. His real genius is revealed in his daring and extravagant use of color and stunning fabrics. He favored the bright, unrestrained palette of the Fauves and fabrics of rich brocade, velvet, and silk embellished with opulent trimmings and furs.

The Folkwear 503 Poiret Coccon Coat, from around 1913, is the perfect example of a very simple design that coveys opulence through drape, shape, and of course, the choice of fabric and trim. The coat incorporates the signature long, unbroken line from the shoulders to the narrow, ankle-length hem while draping in deep, voluminous swags in the back. Its influences are clearly Eastern and yet its look is definitely modern.

Perhaps Poiret’s most lasting influence was in his understanding of the power clothes hold over human desires. He concocted a potion made of cloth and dreams that would lure women into a web of consumerism that has motivated the world ever since.

Designers continue to look to Poiret’s vision for inspiration and his legendary impact has been hard to match. One other showman-designer has dared to try. John Galliano's 1998 Spring Collection fashion show for Christian Dior, held at the Paris’s Opera Garnier, created an intoxicating extravaganza to rival Poriet. While, Galliano's muse for the collection was The Marchesa Casati, is could also be a tribute to Paul Pioret. Below is Galliano's take on the Cocoon Coat, proving Poiret's magic still has the ability to mezmerize and intrigue us still.

Let one man's vision inspire you to make and enjoy your own legendary Folkwear 503 Poiet Cocoon Coat. The printed pattern and pdf version are both on sale throughout the month of October... just in time for cozy couch lounging or a special upcoming holiday occasion. Keep watching for a two part Sew-along blog that will solve the mystery of making your own Ms. Fisher fantasy Coat!

September 30, 2021

By Victoria Watkins

Learning about how embroidery has varied across cultures and historical eras is one of the exciting benefits of developing as a sewist. Throughout our catalog, Folkwear includes many variations of folk and historical embroidery, and our 209 Walking Skirt motif includes one example. I find that I am a person who learns best by doing, and working on this motif has given me a chance to accumulate a little bit of experience in the realm of hand embroidery.

To those new to embroidery, or looking for a refresher on how to transfer the patterns to your fabric, you may want to take a look at our previous blog that demonstrates different methods for transferring your embroidery motifs. Once your design is transferred, you're ready to begin embroidering.

Admittedly, this process was a learning experience for me. It also gave me a deeper appreciation for the accomplished embroiderers of the past, as well as reminded me that sometimes instructions can be flexible guidelines as opposed to unchangeable law. One area I found this to be the case was the first step, in which the directions say to embroider a running stitch a small distance around the marked circles of the motif. Personally, I found it easier to create clean and appealing work once I started experimenting without using this running stitch. Others certainly would find it useful to use them as directed.

The main stitch used for this pattern is a buttonhole stitch, which effectively creates a knot around the edge of the fabric. This in turn allows us to cut out the centers of the ovals and circles, giving us handmade eyelets. I found the most attractive success in pulling the thread tail up toward the center of the circle to tighten the knot, then pulling it back down toward the outside. This seemed to arrange the knots in a way that created a unified and tidy edge.

Once the round was complete, I drew the thread to the back of the work and slipped it behind a couple of the previous stitches, then clipped. This is another point in which I deviated a little from the instructions. They suggest taking tiny stitches to hop from circle to circle so you don't have to cut the thread each time. However, because the brown of the thread was so distinct from the yellow linen, I decided not to do this. If the colors are closer together, I could imagine this being a great way to avoid hassle.

At this stage, it's time to cut out the center, which is a bit nerve-wracking! However, if you've made a tight and consistent circle of buttonhole stitches, you'll find that this is not as terrifying as it initially seems.

It can be a little awkward trying to get scissors down into the taut fabric, so I found that first piercing it with a seam ripper was an effective solution. The instructions also suggest using something like a tailor's awl to this effect. After gently creating a small tear with the ripper, I cleaned up the edges with scissors. This is a step in which it pays to be patient and steady. If you clip too closely to the embroidery thread, you may undo your work and find the entire thing unraveling. However, if you don't clip closely enough, the eyelet is a little ragged on the interior. Of course, this particular example is very stark due to the high contrast between the color of the thread and the fabric base. During this part of the process, I imagined that embroidery that uses matching fabric and thread colors could result in a gorgeous, impressive piece that hides some of the roughness that sometimes characterizes handmade work.

Speaking of roughness, these photos do show the evidence of my initial attempts at this method. While it is a bit vulnerable to show the first shaky steps into a new skill, I hope it also demonstrates something that is part of the reason we are drawn to sewing in the first place. Sewing is a way to expand our capacity for self expression and creativity, and if we don't take the first steps into a new skill without a bold ineptitude, we'll never have anything to show for it. Now after being prompted to tackle this motif as a demonstration, I'm interested in playing around with embroidery at home for personal projects!

If you'd like to play with the embroidery motif featured in this blog post, as well as sew your own Walking Skirt, it's available in both our paper and PDF pattern formats. And the instructions for this embroidery technique are included in the pattern!

Have you dipped your toes into any new techniques lately? We'd love to hear about any learning experiences you've had!

Also, if you want to watch a video of me demonstrating this technique, it is on our YouTube channel (and below).

September 20, 2021 2 Comments

by Cynthia Anderson

In Buttonhole 101: Part One, the basics about buttons and buttonholes was covered. In Part Two we will learn how the relationship between the partners really works.

Once you understand the particulars about buttons and buttonholes, the trick is to understand how to place them so they work together as they should. Once you master the placement, then your machine is left to do all the work.

Patterns are designed with a specific button size and buttonhole placement in mind. This affects fit and proportion. This is important because it also establishes the center front of a garment. You do not want to tamper with the location of the center front.

Using a Different Size Button?

That is not to say that you can not use a different size button than the size designated on the pattern. Selecting a button that is 1/4-inch (6mm) larger or smaller is generally not a problem. However, there will be times when you will want more flexibility when it comes to button size. This adjustment can be applied to sizing a button up or down.

If the size of the button you want to use exceeds the 1/4-inch (6mm) size increase or decrease rule, then adjustments will need to be made to the pattern by increasing or decreasing the finished edge. This adjustment is easy, but needs to be made before you cut out the fabric. A correct adjustment is important because it will maintain the proper fit and proportion of the garment.

Note: Remember if making a woman's blouse the buttons go on the LEFT side as you wear it, which is the side that will be adjusted.

Once you understand the correct proportion between the width of the button, the center front placement of the button, and the edge of the garment it will all make sense. Remember the pattern has been designed to correctly fit a specific size. If you use the pattern required for your size as it is, but decide to use a dramatically different size button than the one suggested on the pattern, two mishaps will happen.

For example: The the pattern calls for a 1-inch (2.5cm) button, but you want to use a 1/2-inch (13mm) button instead. Since the pattern was designed for a 1-inch (2.5cm) button the following mishaps will happen.

Mishap #1:

If you place the button on the center front line like you know you should, then the amount of fabric that extends beyond the button edge will grow from the correct 1/2-inch (13mm) to an incorrect 3/4-inch (19mm). While this might not seem like a large increase, it is. When working with small proportions they add up. In this case it would look strange and like a mistake to have too much fabric extending beyond the button edge. See the illustration below.

Mishap #2:

It is not a good idea to move the button 1/4-inch (6mm) closer to the edge to compensate for the extra 1/4-inch (6mm) of extra fabric width. This creates more problems, because now you have moved off the center front. Not only have the buttons moved 1/4-inch (6mm) off the center, but the size is now off. The circumference of the garment has increased a total of 1/2-inch (13mm). Making an increase of 1/4-inch (6mm) on both the left and right sides of the blouse. See the illustration below.

The Correct Thing to Do

In order to use a 1/2-inch (13mm) button the edge of the pattern needs to be adjusted correctly. The is easy, if you follow the rules.

Rule One: Buttons should ALWAYS be placed on the center line whether on the front or back of a garment. This insures garment will fit correctly when it is fastened and the buttons align down the center front. Otherwise, symmetry and fit are off.

To prevent this from happening, extra fabric is added to the edge. Patterns are always drafted with for a specific button width. The pattern we started with was drafted for a 1-inch (2.5cm) button. But we want to use a 1/2-inch (13mm) button. No worries, forget about the pattern being drafted to use a specific size button and focus on the center line.

Note: This adjustment works for sizing up as well as down.

Ok, we need for the button to not hang off the edge. But since the button is already sitting on the center line, all we need to do is add more fabric to the edge. But how much?

Second Rule: Ideal Proportion Rule: The amount of fabric that extends beyond the edge of the button should be equal to the half of buttons width. It is easy... add the width of the button to the center line to extend the edge of pattern.

This should leave a fabric extension half the width of the button. In this case 1/4-inch (6mm) is visible beyond the button edge. See the illustration Below.

When the garment is fastened, the amount of fabric that extends beyond the button should be half the width of the button as well. For example if a 1/2-inch (13mm) button is sitting on the center front line, the the edge of the fabric should extend 1/4-inch (6mm) from the edge of the button.

Now that the edge extension on the left side has been added correctly, the same extension adjustment of adding the width of the button to the center line needs to be made to the right side. Remember the buttonholes go on the right side. Next, you need to draw out the buttonhole length in the correct position on the right side of the garment.

We already know that the buttonhole length equals the width of the button plus 1/8-inch (3mm).

In this case the length of our buttonhole is 5/8-inch (16mm).

The length of the horizontal buttonhole should extend 1/8-inch (3mm) over or beyond the center front line, toward the finished garment edge. The buttonhole should fall in the same spot as the button.

We have cover a lot, but before you make your final buttonholes lets look closer at the variables of using different fabrics and get some tips to making a successful buttonhole on any fabric.

FabricsAll fabrics differ in the way they behave, which is something you should be prepared for when making buttonholes. Fabrics can be thick, thin, or somewhere in-between; loose or tightly woven; light and airy, stiff, drapey, slippery, or stretchy. Some fabrics are stable which means they do not give, stretch, or contort out of shape. Until you become proficient with making buttonholes stick with stable woven fabrics. They are the easiest to work with and are generally thought to yield favorable results.

However, that is not to dissuade you from working with any fabric you like. Just about any fabric can be made easier to work with using a stabilizer and interfacing.

Interfacing

Interfacing is an additional permanent layer of strengthening material that is sandwiched between two layers of fabric to provide strength. This keeps the fabric from stretching, twisting, and puckering during sewing and adds lasting strength. Areas that include buttons and buttonholes greatly benefit from interfacing for all these reasons. Interfacing is either sew-in or fusible (iron on).

Fusible interfacing can have adhesive on one or both sides. Sew-in and fusible interfacing comes as woven and non-woven versions. They also comes in different weights.

Note: Some interfacing need to be pre-washed. Be sure to check when purchasing.

Tip: If your fusible interfacing is crinkled do not iron it. This does not work. You will end up fusing it to your ironing board or to the bottom of your iron. Non-fusible interfacing iron just fine.

Stabilizers

Extra stability often makes sewing easier, especially when it comes to fine stitching, like making buttonholes or machine stitched embroidery. Stabilizers are added to the outside of your fabric to help make it more stable when machine sewing. After the stitching is complete, the stabilizer is then removed. This works well when a fabric is fine, delicate, stretchy, slippery, thick, or has a pile. Stabilizers come as tear-away and even come as water soluble, allowing the stabilizer to dissolve when wet.

Typically stabilizers are added to the underside of your project, but sometimes it is added to the topside as well. Tissue paper, Swedish Tracing paper, and regular paper can be used a well. Experiment to see what your project needs.

Draw out the placement of the buttons on the left side if making a woman's blouse (as you wear it). And draw out the placement of the buttonholes on the right side (as you wear it).

The placement of the button is determined first, then the buttonhole is place on the center horizontal line of the button. The buttons and buttonholes should align as in the illustration below.

Note: Check the owners manual to see if the bobbin thread needs to be threaded through the hole in the finger of the bobbin. This extra step can make all the difference in the thread tension when making buttonholes.

Make one final buttonhole test if you feel you need to. All that is left is to sew your buttonholes!

Once the buttonholes are made clean up any stray threads by either trimming them away or thread the tails to a needle and pull through to the underneath side of the buttonhole, then tie off. You are almost done.

You did it! Now the buttons need to be added, but first the buttonholes must be cut open. Taking care to not cut into the stitching of the buttonhole is important. The idea is to only cut the fabric slit between the thread beads and tacks.

Tip: Before cutting... Use Fray Check.

Fray Check is a liquid seam sealant that works beautifully to prevent the cut fabric from fraying and keeps threads tidy. Apply the sealant to the entire button hole front and back, or just one side.

Some sewist only apply the sealant to the fabric area that is to be cut using a toothpick. Either apply the sealant before of after cutting the buttonhole open. Be sure to let it dry before cutting if you apply before cutting.

Tip: Be sure to test the Fray Check on a sample buttonhole to be sure the color of the thread and fabric do not bleed. Always allow the sealant to completely dry.

Cutting Tools

There are several different tools for cutting buttonholes and it is worth experimenting to see what you feel the most comfortable using.

Tip: Use straight pins placed on the inside of the tack edge to prevent cutting into or past the stitching.

Hint: If you make more than a small cut using scissors, be sure the half foldline matches up perfectly or you may make an unfortunate cut.

Note: If despite your best efforts, if you still end up with a buttonhole longer than needed or if you decide to use a smaller button, simply cut the buttonhole opening slightly smaller. Back off from cutting right up to the tacks.

Now comes the final anticipated touch... adding the buttons! Hopefully, you now have a solid understanding and can implement everything offered in this blog to insure buttonhole success. If everything went correctly, then all you have to do is sew the buttons where you diligently placed them on the center line.

If you need a refresher on how to sew on flat or shank buttons refer back to the Buttonholes 101: Part one.

It may seem like a lot of information just to make a buttonhole, but that's because details add up for successful results. Learning how to correctly execute buttons and buttonholes will enable you to sew them with confidence and ease no matter the project. It is not uncommon for sewists to sew for years, "winging" their buttonholes. Only after making copious amounts of buttonholes does something finally click... and it all makes sense. It is never too late to master buttonholes or learn new tricks and tips!

September 15, 2021 4 Comments

by Cynthia Anderson

Buttons seem innocent and straightforward enough; however, it is a rare sewist that does not feel a flutter of trepidation when inevitably faced with making buttonholes, especially lots of them. The voice in one’s head taunts, “If I screw up the buttonholes, I will ruin my project and all will turn to sourness and ruin!” For others they consciously or subconsciously avoid patterns that require buttons and buttonholes. The truly afflicted ponder the possibility that their personal sewing aesthetic is more suitable to snaps, hooks & eyes, loops, or safety pins. That is not to say that all the aforementioned do not have their place.

But once you get the hang of buttonholes, you may find they add to the beauty of your sewing. Not only are buttonholes a functional detail, but they can frame and show off a button to it’s fullest, making a garment sing. Buttons and buttonholes are simply hard to avoid if you make clothing. They can be so pretty and add so much.

With that said, no one wants to diligently work on an otherwise happily executed project to have it end in despair because the buttonholes disappoint. The next two blog posts are for anyone who needs to learn buttonhole basics or for anyone who needs a refresher, with a few tips along the way. Buttonholes are not difficult, but they do come with variables you need to know how to handle. Where to place and space them, how they best work together, how to handle when applied to different fabrics, and how buttons actually determine the button/buttonhole relationship.

This month Folkwear is featuring the versatile 133 Belgian Military Chef's Jacket paper pattern or the pdf version. The curved seam construction of this jacket is truly flattering on everyone. The back is semi-fitted, and curves gently to a center point; double-breasted front panels can button to either side. Set-in sleeves are finished with curved cuffs. This is a great fall jacket addition to any wardrobe and a perfect piece for perfecting buttonholes at the same time. The button details truly make the 133 Belgian Military Chef's Jacket special.

Of course there are many Folkwear patterns to that are designed using buttons and buttonholes. For some Folkwear Fall Favorites check out the 202 Victorian Shirt ( and pdf), 216 Schoolmistress' Shirtwaist & Skirt, 222 Vintage Vest, 229 Sailor Pant ( and pdf), 230 Model T Duster, 231 Big Sky Riding Skirt (and pdf), 242 Rodeo Cowgirl Jacket, 251 Varsity Jacket pdf, 263 Contryside Frock Coat, and 270 Metro Middy Blouse (and pdf) , to name a few!

Go ahead and gather the materials needed to make a buttonhole and set them aside for now. And, note that we are only covering making machine-made buttonholes in these next two posts. There are lovely ways to make hand-sewn buttonholes that perhaps we will cover in another blog post.

Materials:

In order to make a buttonhole the correct size you need to start with the button. Therefore, it is helpful to know a bit about how buttons differ in the way they are structured, used, and sewn.

Buttons come in all shapes and sizes and are made out of all kinds of materials including: mother-of-pearl (shell), wood, bone, antler, bamboo, leather, stone, metal, glass, resin, and plastic. They come in all colors and can be decorative or plain.

Buttons typically fall into two categories…flat and shank.

Flat buttons come with either one (antique), two, or four holes and are referred to as buttons with visible holes. They are sewn to fabric through the holes using thread, either by hand or using a sewing machine. Two hole buttons are used for light to mid weight fabrics and four hole buttons are typically used on heavier fabrics or when extra security is needed.

For a flat button to sit properly, it should be sewn so it rests just above the buttonhole when fastened. To achieve this extra bit of space, a little shank is made by slipping a sewing needle or toothpick between the underside of the button and the fabric it is to sewn to.

With the button slightly elevated above the fabric a thread shank is easily created when sewing the button in place. This extra bit of space allows the two layers of fabric to sit comfortable under the button. This thread shank also gives the button a little movement and prevents abrading the fabric. Make the shank by making a few passes with the thread through the button and fabric and then wrap the thread underneath the button around the threads a couple of times for strength.

They are sewn to fabric by hand sewing, using a needle and thread that passes through the shank hole and into the fabric. Shank buttons are generally used on heavy and thick layers of fabrics, but not always.

Note: For shank buttons, the shank should be positioned and sewn with the shank running parallel to the buttonhole, both for horizontal and vertical buttonholes.

Hint: If using buttons on the back of a garment, flat buttons are going to be more comfortable. Simply consider if you would want to lean back on or sit on a button that has a shank or is rather thick, or large.

Yes, buttonholes have anatomy and it helps to understand it. Not all machines make buttonholes in the exact same way. Machines can use a one-step or 4-step method and those methods can vary in how they are executed. But no matter the way a sewing machine sews it's buttonhole, the anatomy is still the same.

Buttonholes use two parallel rows, or beads, which are created with an extremely short zig-zag or satin stitch, connected at each end with a longer zig-zag stitch called a bartack.

The thin channel of fabric between the beads is slit open for the button to pass through. A buttonhole is actually a cut in the fabric framed by stitches to provide integrity and stability.

Note: Buttonholes are never made on the wrong or back side of the fabric because the bottom tension thread will then be visible and you don't want this.

The illustration below shows the typical four-step buttonhole method. In this example the stitching starts at the back of the machine and moves forward. The red portion with the arrow indicates the stitches sewn at each step in creating the buttonhole.

Note: that some machines start their buttonhole stitch from the front to the back.

The most common buttonhole offered on today's machines are the Standard, No Bartack, Keyhole, and Top Bartack.

The Standard buttonhole is the most common and works nicely on mid- to heavy weight fabrics. This style of buttonhole is offered on all sewing machines.

The No Bartack buttonhole is rounded on both ends. This design works well on fine fabrics such as silk, because the round edges do not damage the delicate fibers of the fabric.

The Keyhole buttonhole is best used on heavy fabrics when using thick buttons or buttons with shanks are used. The shape of the “keyhole” enables the button to pass through the thick layers of fabric more easily. Coats and jeans often have this type of buttonhole.

The Bartack buttonhole is used on fine to mid-weight fabrics. This style is often found on children’s clothes and finer women’s garments.

Depending on the machine, some offer lots of buttonhole options, while others may be more basic. For our purposes we will focus on using the Standard buttonhole.

Buttonhole sizing depends on the size of the button. Sizing generally refers to the length of the buttonhole. To create the correct buttonhole length, a button’s diameter (width), thickness of the button, and whether it has a shank, should be taken into consideration.

Buttons come in standard sizes including; 1/4-inch (6mm), 5/16-inch (8mm), 3/8-inch (9.5mm), 1/2-inch (13mm), 5/8-inch (16mm), 3/4-inch (19mm), 1-inch (2.5cm), and continuing on up. There are no hard and fast rules when it comes to which size of buttons to use. But typically, smaller buttons are used on shirts and fitted blouses and children’s clothing. Garments like coats and jackets are often made from thicker fabrics and need heavier and larger buttons.

To determine the size of the buttonhole, measure the width or diameter of the button and add an extra 1/8-inch (3mm). This extra 1/8-inch (3mm) makes the buttonhole a tad longer, helping to ensure there is enough room for the button to pass through the buttonhole. Both horizontal and vertical buttonholes receive this additional length. Vertical buttonholes receive the additional 1/8-inch (3mm) at the top of the buttonhole. Horizontal buttonholes receive length on the finished edge of the garment.

The thickness or height of a button matters too. If the button is thick or domed, the buttonhole opening will need another tad more length to make the opening larger. Add another 1/8-inch (3mm) and test.

Now that you know how to determine the size of a buttonhole, make a test. Draw a line the length of your buttonhole on the right side of the fabric, using a pencil or fabric pen like the illustration below. For now, do not worry about positioning, just sew a buttonhole the length you marked. Draw a line like the one below.

Note: When making the final buttonhole guideline you will want to use a non-permanent method, like a heat sensitive or water soluble pen (water erasable marker) made for this purpose. Or make a Tailor's Tack by using a needle and single thread to create the line. Remember that buttonholes are made on the right side of the fabric, so you don't want the guideline to be visible.

Now test making a buttonhole using your machine according to instructions in the manual. Push your work under the foot and place your needle exactly at the buttonhole start. Set the stitch spacing according to your manual instructions. Align the guide on the foot with the drawn line, to keep the buttonhole straight. Keep practicing making different lengths. Adjust stitch width as necessary depending on the length.

Note: If your fabric seems to drag and not move easily when stitching the buttonhole, lengthen the stitch. If the stitch is too small or tight the feed dogs can have difficulty moving the fabric as it should.

Tip: Test the buttonhole to be sure the button will easily pass through the cut opening. Nothing is more frustrating than the thrill of beautifully executed buttonholes, only to then discover that they are too small for the buttons.

Now that you have successfully made a test buttonhole. Lets play around with button placement as a design element.

How many? This depends on how many buttons you have and how many you think look aesthetically pleasing. Typically buttons don't look very good spaced too far or too close together. But this is up to you.

Hint: Some sewists like to use an uneven number of buttons, but that is personal preference.

Take the time to experiment with different configurations and spacing possibilities. Buttons can be evenly spaced or grouped. A pair of tiny buttons can be treated as one button, spacing them just far enough apart to set each pair off. I have a thing for copious amounts of tiny shoe buttons running down the front of a vintage inspired blouse. Depending on the garment and size, four or five evenly spaced can be all the buttons needed. Buttons can make a statement or have a more subtle effect depending on the button and color of thread used used to frame them. If you are feeling adventuresome, mix your buttons up! How you use your buttons is totally up to you.

Hint: If you want your buttons understated, use a thread that blends with the color of the button and fabric.

Use a Simflex (folds like an accordion), for more accurate spacing of your buttons. Or simply space your buttons out freehand to get an idea of what appeals to you and then use a ruler for accurate spacing.

Note: The rule is, typically ,that women’s blouses buttonholes on the right (as worn), which means the buttons go on the left. Buttonholes on Men’s shirts go the left (as worn). To help you remember… just remember “women are always right.”

There are strategic considerations for where to start and spacing buttons. Below are a some scenarios to help you get started:

Note: Top buttons are generally placed 5/8-inch (16mm) down from the top edge of the garment at the neckline, depending on the size of the button.

Note: Buttons are not usually positioned close to the bottom edge of a garment. Men’s shirts vs women’s blouses are a good example to study. Keep in mind whether you will wear the garment tucked into a bottom garment or worn loose.

Hint: Don’t neglect other places that buttons could be placed. Cuffs, collars, and tabs come to mind. Use the same the aesthetic through out your project, making your garment cohesive and harmonious.

Because buttons are always placed on the center line, it is the buttonhole that must be positioned correctly either horizontally, vertically, or at an angle to work properly with the button. Each position has it’s own advantages and reasons for doing so. Angled buttons are more complicated, so we will leave them for now, and focus on horizontal and vertical buttonholes.

Hint: Sometimes the top and bottom buttonholes will be sewn horizontal to serve as more stable anchors. The top buttonhole on a man's shirt is often sewn horizontally.

Hopefully, you have learned some new things about buttons and buttonholes, but there is more to come. In Part: Two of this blog you will learn how the button and buttonhole come together to create a functioning detail.

The Folkwear 133 Belgian Military Chef's Jacket is not only a great wardrobe addition for fall, but also the perfect opportunity to try your new buttonhole knowledge. The pattern is available as a printed version or pdf and both are on sale throughout the month of September. Purchase your pattern just in time for the next blog installment Buttonhole 101: Part Two, where we will finish up all you need to know to make lovely buttonholes.

August 22, 2021 1 Comment

August 15, 2021

by Cynthia Anderson

This month Folkwear is featuring the 216 Schoolmistress Shirtwaist & Skirt Pattern. These garments date from around 1907, a time when women's clothing became more man-tailored which was a new and exciting twist in women's fashion.

In case you were wondering, a shirtwaist is a blouse. Shirt, but to the waist*. This type of fitted blouse appeared as early as 1890, making it one of the first fashions to originate in America. This humble beginning of men's tailoring being added to women's wear would launch an aesthetic that would make the careers of many modern designers to come.

The pieces featured in this pattern are both elegant and flattering, and deceptively easy to construct. The beautifully blended details of the blouse are varied on the front and the back, providing delightful surprises coming and going! The pattern allows for two front facings versions, one simple and one uniquely scalloped. Two sets of wide tucks extend over the shoulders framing the scalloped facing on the front and then converge in a lovely v-shape at the waist shaping tie detail, that finishes with a small gathered peplum on the back. The gored skirt included in the pattern is an elegant companion to the shirtwaist and it is worthy of more attention and will be featured in a separate blog post.

In this post I will focus on the making of the scalloped front facing of the shirtwaist. This detail is not hard to make and should not be missed! Once you give it a try you will not be able to resist adding this tailored touch to other worthy projects. Learning to make this unique detail is satisfying and enjoyable.

The turn of the century was a time of change for women and their clothes changed in tandem. As capitalism took hold in Western society, work shifted from family, home-based businesses to larger endeavors. Many women were working for pay outside the home for the very first time, and engaging in active sports like never before. Along with this new found sense of independence came the need for practical clothing that had long been the the privilege solely of men. The shirtwaist design allowed for practical mobility with tailored details adopted from men's clothing, while still retaining the feminine aesthetic.

This pattern was originally taken from a matched set made in white cotton with tiny squares woven with black thread. Using the same fabric for both a top and a bottom was popular during this time. This matching pairing was referred to as "shirtwaist suits." Unless a woman was wealthy, her wardrobe would have been limited to a few cherished pieces that were worn regularly. Making a shirtwaist and skirt out of the same fabric allowed for a coordinated look, while the separate pieces had the added benefit of practical interchangeability allowing for a more diverse wardrobe. This idea of how to build a wardrobe is one we still abide by today.

Fabrics

Originally the shirtwaist and skirt would have been made of cotton, linen, light weight wool, silks, taffeta, gingham, percale or organdy. Due to the tailoring details of this design, fabrics that will allow for crisp edges, while allowing for a soft drape are ideal. Look for fabrics that are fine, densely woven, and light to mid-weight. Cotton lawn, batiste, and shirting would be just as perfect now as they were at the turn of the century. Cotton flannel and light weight wool would be perfect for winter. For a dressier look silk would be amazing.

The details of this shirtwaist allow for a prefect opportunity to get creative. Cut the collar, facing, cuffs, and ties on the bias for a creative use of a fabric with a stripe or directional print. Mix solids, stripes, and prints in anyway that makes your heart sing. Even mix up the types of fabrics - just remember to make the fine details out of fabrics that will not try to unravel on you. And always launder different types of fabrics before combining them.

Getting Started

This shirtwaist is not difficult to make, but the goal of this blog is to give you some tips and techniques that will ensure you achieve the clean finish that the scalloped front focal point requires.

In this demonstration I am using cotton muslin with contrasting red thread to make the techniques easy to see. I am not constructing the entire blouse... just the front (View B) using the scalloped front facing on the right side only.

To make the scalloped front cut one single layer of fabric for each Front piece. Typically the front of a blouse is cut two pieces at the same time. But, this is where the pattern is a bit different and each side of the front is cut separately due to the scalloped edge of the right side. It will help to trace off a separate pattern pieces for the right side and the left side for this pattern since they are layered on top of each other. The left side is also wider than the right side as it creates its own facing.

I cut the LEFT side of the front first, with the pattern placed right side up on the right side of the fabric. For the RIGHT side I flipped the pattern over (writing side down), placing it on the right side of the fabric. This should result in mirroring Front A pieces as in the photo below.

The RIGHT side of Front A will receive the Front Facing C. Notice (as mentioned above) that the Left side is wider than the right side. This is because the Left side of Front A will fold under creating it's own built in facing. This facing goes together in nifty unexpected ways.

To reduce confusion I have labeled the right and left sides (as you wear them and according to the pattern pieces) with a bit of masking tape on the right sides of the fabric.

Working on LEFT Side of Front

As always, it is a good idea to staystitch any curve. Make a staystitch along the scalloped edge of the Left Front just within the 1/4 inch (6mm) seam allowance. This staystitch will not only provide stability to the edges, but will serve as a fast and easy guide for turning and pressing the edges under. The photo below shows the wrong side of the Left Front facing up.

Notice the drawn fold line (in the photo below) was also added to the wrong side. I will use it make a long basting stitch, to use as a folding guide and remove later. See the next photos.

Now, clip the inside of the curves to release the fabric so it will turn under smoothly. Trim the points so they will eventually be nice and crisp when turned. Notice how small the clips are in the photo below. The tighter a curve, the finer the clip should be. Remember clips are made to release the weave of the fabric so smooth curves can be achieved. If your final curve is not as smooth as you would like, simply go back and clip a bit more.

Press under the edges using the 1/4-inch (6mm) staystich as a guide. Since the turned under edge is small, use your fingers to help get the folds started and to crease the fabric before pressing. It is not necessary that your staystitch guide line be absolutely perfect. The idea is to give yourself enough of a guide to allow you to keep the curves smooth. Adjust the folding and pressing until you are satisfied with the results.

In the photo below the pressed curve is seen from the right side facing up. Even though this edge will be turned to the inside of the Shirtwaist front and will be hidden from view, it is nice to have it neat.

Using the straight basting stitch as a guide, fold the Left Front under to the inside. Pin and stitch close to the edge of the pressed scallop edges. Continue stitching along the straight portion to the bottom edge of the the shirtwaist as well.

Note that using shorter stitches when stitching curves is beneficial, because the smaller stitches are easier to control, they make a sturdier and more stable stitch line and hold, and generally look nice and neat.

When stitching the scallops, try to pivot at the tip of each point for a smooth finish. Small or short stitches will make this easier.

The photo below shows the stitching is visible on the right side of Left side of Front A for a beautiful finish. Even though this finish will not be seen from the outside of the garment, it is a delightful secret touch for the wearer!

Working on the RIGHT Side of Front

Now, orient the Front Facing C as shown below. Take notice that the points to the scallops face right, with the right side facing up. Staystich along the smooth scalloped curves on the left side of the Front Facing. Clip the curves as seen below and as indicated on the pattern. The idea is to clip up to the curve cleavage, staying inside the staystitch.

Reorient the facing again. Working with the WRONG side of Front Facing C facing up, use the staystitching as a folding guide, being sure to fold and press the edge towards the pointed edge of the scallops (similar to what we did with the left side front).

Pin and stitch RIGHT side of Front Facing to WRONG side of the Right Front, using a 1/4-inch (6mm) seam allowance (NOT the usual 1/2-inch seam allowance). You should be stitching the pointy edge of the scallop edge. Remember the facing will be turned to the right side of the Right Front... not the wrong side as you normally would.

Clip inside the curves and trim off the points as before. Be sure to carefully trim the points as seen in the third photo below. A clean and close trim will ensure the point turns cleanly, resulting in a sharp point.

Now this is the exciting part! Turn the facing to the outside (right side) of the Right Front. Working with the right side facing up, press the curved edges with a slight roll towards the inside of the garment. The idea is to roll the edge just enough that the stitched seam is not visible on the right side of the garment. Use your fingers to make a sharp tip on the points before pressing. Try to avoid any turning tools on the points because you are likely to stretch them in an unfortunate manner. If you made your curve clips small enough and point trims close to the stitching, then the crisp edge should easily be achieved. This is a craft detail that will make the shirtwaist scalloped front a delight to wear and behold!

One last bit of stitching to go. Pin the facing to securely hold it in place for stitching. You may or may not want to hand or machine baste the facing in place before making the final top-stitching. The final top-stitching serves as a construction element, holding the facing in place and it can also be a final decorative detail if you like.

Top-stitching is typically made with a longer stitch than a construction stitch. However, longer stitches can be tricky on curves and at pivoting points. Luckily, this final bit of stitching is done on the smooth side of the curve and points are not an issue. I recommend cutting a second Front Facing C piece out of the fabric you are using and experiment with the top-stitch length before attempting the final curves. This will enable you to gage the best stitching length. Once you have decided on your top-stitch length, consider whether you want your stitching to blend in with your fabric or stand out as a design detail.

Even though this demonstration was just made out of muslin, you can see how delightful the details are on the front of the Folkwear 216 Schoolmistress Shirtwaist and how a bit of top-stitching can make a project special. Don't forget about how good the buttons are going to look! Of course, if your stitching is especially fine, use hidden snaps to keep the front clean and simple.

Below are the final photos of the muslin demonstration. I hope this blog post will encourage you to try the scalloped front facing for this truly lovely shirtwaist blouse. If you like the front detailing... just have a look at the back. This is a special piece, so prepare yourself for all the compliments to come.

Purchase your pattern early so you will be ready to enjoy wearing the 216 Schoolmistress Shirtwaist come fall. Pair with your favorite jeans or make it's companion skirt. This shirtwaist blouse and its unique details will surly be a welcomed addition to anyone yearning for a touch of feminine romanticism when the temperatures turn cool and crisp... no mater whether you head back to school or just because.

Don't forget the 216 Schoolmistress Shirtwaist Pattern also comes with a beautifully constructed gored skirt. The skirt design is a perfect romantic companion piece to the shirtwaist and a must to make just because it is so versatile and stunning. In a separate post we will show you how to grade this gored skirt between sizes to help you achieve a perfect fit.

-----------------------------------------------------------

*We try not to get too intense on the interesting etymology of garment words but this is hard. Suffice to say that the word 'shirt' was once used for a garment that continued down below the waist. We would now use the word 'shift' or 'slip' or 'chemise' for this type of garment. Adding 'waist' to the word, 'shirtwaist', denoted a garment that ended at the waist. Shorter, waist-length 'shirts' are a relatively modern invention.

This is much like the word 'waistcoat' which we would now just call a 'vest'. It was the word 'coat' (coat/cloak) which was a long garment worn on the outer layer, with the word 'waist' to identify that you stopped the garment at the waist. We are not going to go on and on with the extra geeky-info that waist/vest are related words.

August 04, 2021 4 Comments

Got a Cowgirl spirit? Then you definitely need the Folkwear the 243 Cowgirl Skirt to channel that energy! Whether heading for a wild rodeo, saloon, country picnic, or dance floor this Western-styled skirt has lots of flair. This skirt has all the details needed and then some to make an everyday or a fun occasion piece. This easy to make pattern is on sale all month. The Folkwear 243 Rodeo Cowgirl skirt comes as a PDF Pattern.

Both Views included in the pattern feature a flared A-line silhouette, shaped waistline with front and back darts, waist facing, lace-up back closing, and several easy-to-apply hip yoke shapes for fun. View A sports a shaped hem applique. View B has a swishy hem flounce and hip/pocket yoke.

For the perfect cowgirl fabrics to make the skirt consider denim, cotton, linen, suede, leather, lace, or silk. Then add your personal cowgirl statement in fringe and embroidery or studs and applique patches, to create an adventurous collection of skirts for everyday, weekend, and party wear.

Every cowgirl knows that a true cowgirl skirt needs a sassy swish of fringe! Customizing your skirt with fringe is easy and fun to do. Fringe trim can be found ready made or easily make your own. Keep reading to learn to make your own fringe!

Either dress your skirt up or down depending on your mood. Even change the fringe out for another color. Fringe can be applied to the wrong side of your garment, just under the hem edge or other edges. Use a quick and easy whip-stitch to secure the fringe. If you decide to remove the fringe... then just snip the whip-stitch and wear sans fringe for a simple everyday look (see photo below). Dress up your cowgirl skirt or not... adding fringe is easy and commitment free!

Make Simple Fringe

To make your own fringe, cut strips of fabric 4-inches (10cm) wide, along lengthwise or crosswise grain. With chalk or thread, mark the 1/2-inch (13mm) stitching line along one edge. Cut the fringe ends 1/4-inch (6mm) wide, stopping at the marked line. During garment construction, sandwich the fringe strip between pieces being stitched together, matching the raw edges. Insert purchased or custom fringe in any seam you desire or topstitch to finished seams or hem.

Tips for Fringe Making

Happy Trails!

July 28, 2021 2 Comments

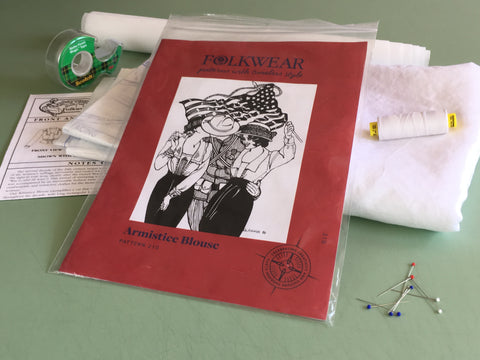

In this blog post the 210 Armistice Blouse will undergo a few simple modifications to turn it into an everyday summer wardrobe staple. Make as simple or embellished as you like, the Edwardian Charm is not going anywhere. Just shortening the sleeves and turning it into a pull-on version does the trick for making the 210 Armistice Blouse into a refreshing top to beat the heat!

Check out the post, 210 Armistice Blouse... a Symbol For Change, for a bit of inspiring history to help get you started in what will become a new favorite summer top.

I am making this version of the Armistice blouse, with a nod to it’s history by using white handkerchief linen and adding a few small tucks to embellish the Vestee. I am also using French Seams as Edwardian women would have. Since I am demonstrating how to make a pull-on-over-the-head design, the Vestee is sewn to the front of the blouse on both sides, eliminating the need for buttonholes and buttons. However, you could add buttons for decorative touch? To keep the top loose and comfy I have decided to leave off the back shaping tie. However, there is no reason not to include the tie on the next version. The sleeves will be shortened. And I need to add a bit of length too.

The Armistice Blouse was traditionally made of light-weight gauzy linen and cotton fabrics. Keep in mind that these early Edwardian blouses were worn with sometimes two or three layers underneath, which helped to prevent see through. Just keep the fabric opacity of the fabric you chose in mind. Though sheer fabrics are a lovely excuse to add a dainty camisole underneath.

White was the color de jour for fabrics and synonymous with the Edwardian period (See 210 Armistice History blog to learn more), that is not to say that colored fabrics, as well as prints and stripes were were not popular too. Take a good look at the lovely use of white stripes used in the version below.

Just about any woven fabric is an excellent choice for making this blouse for modern wearing. Since we are focusing on a summer version, light weight to mid-weight fabrics are ideal. To achieve the crisp-airiness of the original designs look for light-weight cottons, like cotton batiste, voile, lawn, broadcloth, shirting, seersucker, and eyelet.

Of course, you can not go wrong with handkerchief linen. Consider light-weight silk like haboti or cotton and silk blends as well. For a truly comfortable fabric and in keeping with the soft Edwardian-look, pick a fabric with a nice soft drape. If you like the idea of naturally dyed colored cotton and linen fabrics with eyelet laces and ribbons to match check out www.botanicatinctoria.com.

Making Pattern Adjustments

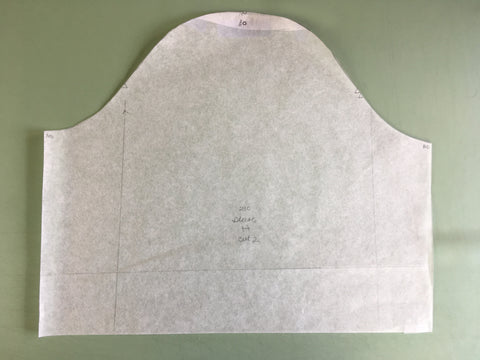

To get started I need to make a few pattern adjustments first. I am adding 1/2-inch (13mm) to the length of the size medium. That means I need to add a 1/2-inch (13mm) to The Front A, Back B, Front Facing F, and Vestee C pattern pieces. The sleeve is simply cut to the length I have decided on, including the hem.

Adjust Vestee to Accomodate Hoizontal Tucks

Even though the pattern comes with a vestee pattern piece with vertical tucks, I want to add horizontal tucks to my vestee. Folding up the fabric to make tucks takes up the length, so I need to accommodate for this by adding more length. But how much? Well that depends on the width of the tuck. I am using five 1/4-inch (3mm) tucks. When folded each tuck takes up 1/2-inch (13mm) of fabric "real estate", so to speak. This results in 2 1/2-inches (6cm) being used up to create the five tucks.

That means I need to add back the 2 1/2-inches (6cm) to the orignial length of the size medium. Plus, the 1/2-inch (13mm) I decided to add to the blouse length.

To keep the vestee approximately the width the pattern intended, use the extra width at the foldline as the seam allowance. The idea is to have 1/2-inch (6mm) seam allowance on each vetical edge of the vestee. (See the photo above).

Cutting Out the Pattern

To keep this version of the Armistice blouse simple, I am eliminating the need for pattern pieces; Tie D, Turn Back Cuff J, Cuff K, and Placket I. And I am not using the wider vertical tucked version of pattern piece C.

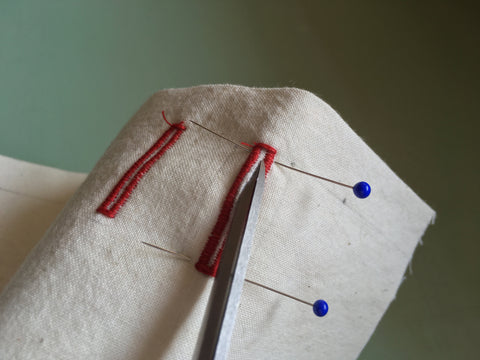

Decide on Seam Finish Before Starting Construction

Once all the pattern pieces are adjusted and cut out, decide how you want to finish the seams? The Armistce Blouse is a perfect project for using French Seams. The use of French Seaming was popular in Edwardian garment making. Before sewing machines were available, fine French Seams were sewn by hand. Luckily, French Seams can easily be made using a sewing machine. This technique is not hard, creating a strong encased seam, with a lovely finish. Using French Seams is a way to celebrate a historical technique that is still considered fine craftswoman-ship today. French Seams are ideal for fine fabric seamwork. So consider giving French Seams a try using Folkwear's 210 Armistce Blouse Pattern!

Use the usual 1/2-inch (13mm) seam allowance and finish the seams as you like... if not using French Seams.

Note: French seams are not used for all sewing construction needs. Typically, only the shoulder seams, side seams, and the sleeves seams are made with French Seams. Sleeves that have a tight curve at the shoulder can be tricky, resulting in a finished seam that will not lay nicely and may pucker-up. It is perfectly ok to pick and choose where French Seams work best.

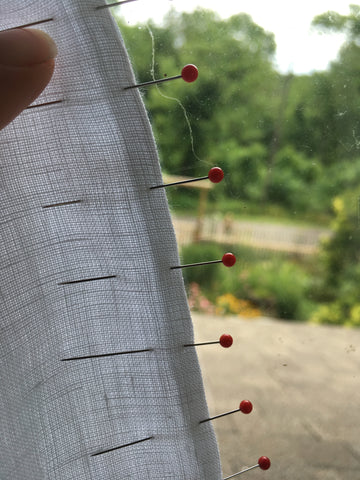

French Seam Shoulder and Side Seam Construction Using 1/2-Inch (13mm) Seam Allowance

French Seams are made by starting with the WRONG sides of the fabric together... NOT right sides together, as you normally would. On the raw edge of your work, align and match any notches, stitch a scant 3/16-inch (4mm) seam. Press the seam to one side (either will do). Turn right sides together, encasing the tiny seam, and press the edge neatly or pinch the fabric with your fingers to create a clean edge. The tiny seam should be sandwiched between the two layers of fabric. Then stitch a 5/16-inch (8mm) seamline, taking care to avoid catching the tiny raw edge encased in the fold.

The idea is to only use up the amount allotted for the seam allowance. In this case the seam allowance is 1/2-inch (13mm). You will need to adjust your French Seam calculations depending on the width of your seam allowance and how small you want the finished French Seam to be. Experiment with different weight fabrics and varying seam allowances widths to see what the limitations are. Extremely small French Seams were a badge of pride and craftswoman-ship for Edwardian sewists.

Before the shoulder seams are made, the gathers at the shoulders need to made first. Make two rows of gathering stitches outside the 1/2-inch (13mm) seam allowance as indicated on the Front A pattern piece. Pull the gathers up so that the Front fits the Back at the shoulder, pin to hold in place then stitch the seam allowance. Remember... wrong sides together and a scant 3/16-inch (4mm) seam if making French Seams.

Below is a view with wrong sides together and the scant 3/16-inch (4mm) seam. The gathering is made below the 1/2-nch (13mm) seam allowance.

For the French Seam just press to either side to prepare to stitch the next step.

The right sides turned together with the scant seam sandwiched in between the two layers of fabric. This is where the right and wrong sides can get confusing, but follow along.

The Scant seam allowance should be neatly encased in the final seam.

Sew the next stitch line at 5/16-Inch (8mm). Besure to back stitch at hte beginning and ends of the stitchline.

Repeat for the opposite shoulder seam.

Sew the side seams now as you prefer. Side seams are perfect for French Seams, so use the same technique as above.

Notice below, the side seams are pinned with wrong sides together. The gathered seam at the shoulder is rightside facing up.

Stitch a scant 3/16-inch (4mm) seam.

Turn the right sides together sandwiching the scant seam allowance inside.

Stitch the next seam allowance at 5/16-inch (8mm ) on the wrong side.

Press the side seams towards the back.